Archaic Rendering

By Jaakko Pallasvuo

Berlin, May 2011. I’m at an opening for Brand New Paint Job Extended, an exhibition by net artist Jon Rafman. A performance is about to begin. This is the last time I’m doing this, Rafman announces.

Screen-captured footage from Second Life is projected onto a wall. We see Rafman’s avatar: a gigantic, poorly rendered Kool-Aid Man. The camera pans around a lush forest while Rafman talks about what he has seen in his virtual travels. Second Life is an online world crafted by its users. It contains concert venues, natural wonders, dream homes and sex clubs. Rafman has observed it.

Kool-Aid Man kneels down in the forest and raises a sword. He ceremonially disembowels himself. The video goes on to show Rafman canceling his account. To emphasize the moment a DVD containing the video is ejected and crushed. We have witnessed a ritual suicide. There is applause.

A few hours later the temptation to repeat the gesture has grown strong. Another DVD is inserted. The video is shown and narrated again. The second DVD is also destroyed. I pick up a fragment of it.

I’ve just read The Work Of Art In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction. It’s never too late. I wonder what Walter Benjamin would make of our Post Internet predicament. Benjamin committed a less ceremonious suicide in 1940, after spending his last years in exile from Nazi Germany. I read about his life on Wikipedia. It’s intriguing and far from my personal experience.

The Work Of Art In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction, an essay written in 1936, was first translated into English in 1968 and has gone on to become an extremely influential text. Benjamin describes the connection a work of art has to the (technological) means surrounding it. How the reproduced work of art is to an ever-increasing extent the reproduction of a work of art designed for reproducibility.

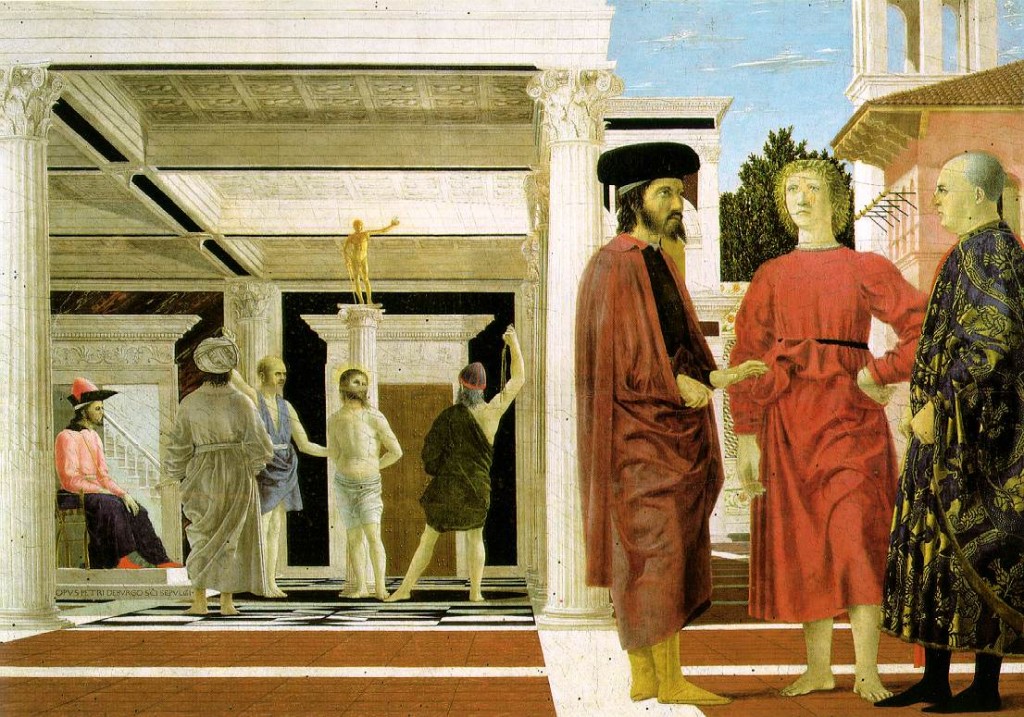

Benjamin writes about the aura of a work. A certain genuineness. This refers to a work of art’s unique existence in the place where it is at this moment, to its changing physical structure, and to the fluctuating conditions of ownership through which it may have passed.

The social conditions surrounding the work are key. They define how it’s perceived. What function it serves. To Benjamin, a work of art only has an aura if it is embedded in ritual.

Benjamin’s point of view is difficult for me to grasp. I get how he constructs an argument, how it has filtered through to countless other texts. What Benjamin articulates well is his position between the dreadfully old and the terribly new. The future we live in doesn’t lend itself to such compact dichotomies though. Modernism is an ongoing, faltering project.

What we see in 2011 is an art world deeply invested in large-scale, high-price work. Art objects exist for their own sake or for the service of global capitalism.

I find it interesting when artists who effortlessly inhabit online space pour effort into manufacturing IRL uniqueness. Weirdly enough, this usually happens through the printing process. Ephemeral, flexible digital content is reduced to c-prints, prints on canvas, prints cast in resin, prints on pillows and so on. These are trophies. They exist to commodify, to give physical structure, duration, history. Perhaps to claim some aura for themselves. This process caters to the demands of a gallery/museum system no one seems to have a kind word for. Careerism is masked by an adopted playful nonchalance.

Rafman’s avatar ceased to exist through an emulated Seppuku, a ceremony with both spiritual and political resonance. But death in the virtual means very little, and with nothing at stake it’s easy to collapse into irony. Will pathos be reintroduced during the century? What political/social/ecological catastrophe will drive us to actual ends?

I began to engage with net art because it annoyed me. I took that as a sign that there was something there. The good and bad sides are the same: programmed nowness makes pieces exciting and makes me think they’ll soon go out of style and relevance. There might be exceptions.

Rafman’s work leans on current aesthetic and software, but reaches beyond it too. It’s about being in awe of the world. Romantic in general disposition, and in relation to the 18th century. Online drama tarnished by sentimentality, doubt, nostalgia. It’s something I can identify with. If it will last is another question altogether.

It is possible that someone in another age will try to engage with Rafman’s work like we do with Benjamin’s writing. What is cutting edge for us will soon be archaic rendering. How will their knowledge of future triumphs and disasters alter the work? There’s no way of knowing if we’re in the beginning or the end.

Another work by Rafman,You, the World and I (2010) unfolds as a video where an anonymous narrator desperately searches for a lost love. It shares a deflated, melancholic humor with the Kool-Aid Man performance. Instead of going out into the world to find his love, the narrator makes use of Google Earth and Google Street View. He browses endless streets, looking for a glimpse of her. Instead of finding her he finds a pixelated reproduction. A photograph of her standing on a beach. Maybe that’s enough.

Comment

Issues

- August 2011 (10)

- July 2011 (10)

- June 2011 (10)

Recommended reading

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Avec Bonus Sans Depot

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Online Casino Canada

- Trusted Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Sites UK Only

- UK Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Best Online Casinos UK

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Betting Sites That Are Not On Gamstop

- Migliori Casino Online

- Top 10 Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Meilleur Site Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino Online Esteri

- Paris Sportif Ufc

- 仮想通貨 カジノ

- Top Casino En Ligne

- 코인카지노 사이트

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Français

- Siti Scommesse Non Aams Bonus Senza Deposito

- Meilleurs Casino En Ligne

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Site De Casino En Ligne

- Siti Non AAMS Sicuri