06.04.11

Why Are There No Great Women Net Artists?

Vague Histories of Female Contribution

According to Video and Internet Art

Since the women’s liberation movement, various gains and losses have occurred in regards to the representation of women in art.[1] In its infancy, women artists co-opted video as a mass medium for channeling affective and durational realities. Eventually, the migration of video to immaterial digital format and the decentralized distribution of the internet has had implications for its curation and appreciation. While sexism in the art world is an old, ongoing problem, the popularization of “web 2.0” technologies have allowed a previously readerly cyberpublic to become active contributors to online content.[2] By tracing a history of disparate moments in which female voices and contributions were recognized in the media arts, I will compare previous feminist efforts and existing works by women to uncover the causes for the ongoing underrepresentation of women in internet art.

To set the stage for this inquiry about representation of a group within a specific genre (woman internet artists), I define feminism as a method of asking questions about female perspectives in relation to traditional ideas of masculinity and femininity. It is not sexism, nor is it a subject position.[3] In 1972, Linda Nochlin’s seminal essay “Why are there no great women artists?” claimed that cultural and educational institutions prevented women artists from advancing equally as male artists.[4] Almost two decades later in 1996, Steve Dietz likened the state of net art (interchangeably called “net.art” at the time) in the museum or gallery to the marginal state of feminist art perspectives before 1970s in “Why are there no great net artists?”[5]

Joan Jonas, Vertical Roll, 1973.

Early Feminist Video

In the late 1960s, the second wave feminist movement coincided with a significant introduction of female voices into video art in North America (along with an increase in female literacy levels, spending power, and sexual liberation following the innovation of the birth control pill). Women artists introduced personal politics in the intimate and immediate medium of video after the advent of the PortaPak in 1965. By directly addressing the camera in a confessional or actively gazing manner, women imparted agency in telling the stories of their lives in the way they would like to be represented. Endurance performance, storytelling, reenactment and reappropriation were common amongst female videomakers. Such a direct mode of address shifts over the course of the next two decades as MTV debuts in 1981 and YouTube in 2005. With the varying representations of women came a greater degree of revolt, parody and subversion.

Marina Abramovic, Rhythm 10, 1973.

Despite video’s potential for empowerment and intimate storytelling, canonized feminist video have highlighted dialectics of gender with regards to the “nature” of a woman as sensual, personal, and emotive.[6] When such characteristics are placed in opposition to those of traditional masculinity (as stoic and rational), the regime of representing women in feminist video programs become stereotypical and patronizing. Conversely, Marina Abramovic’s performances always express a disciplined composure. In Rhythm 10 (1973), she lays out 20 sharp objects and repeatedly stabs them between the spaces of her splayed fingers. Acting in a task-driven and ritualistic manner, Abramovic motivates viewers to forget one’s imagination of her as a woman, and acts as a performer. She is first an artist, and then a woman.

Steina Vasulka, Warp, 2000.

Petra Cortright, swickoof.mov, 2011.

Combining formal conventions with figural content, artists such as Joan Jonas explored the properties of the medium in relation to the existing technical innovations during their time of making. In Vertical Roll (1972), the structural convention of transition by vertical roll is employed repetitively as a formal device throughout a twenty-minute performance. An equally pitchy noise that syncs to the movement of the transition, the constant fragmentation of the video image prevents the viewer from seeing Jonas completely. Similiarly, Petra Cortright’s webcam performances echo the tradition of presencing the self for the camera. The interlace-glitch effects in swickoof.mov (2011) recalls the conversion of formal gesture into a visual manifestation of manipulated signal in Warp (2000) and Violin Power (1978) by Steina Vasulka.

Likewise, Brenna Murphy’s yingyyangyhuman (2011) utilizes rapid editing between recorded images of herself to address the variable properties of the digital medium.[7] Cutting back and forth between horizontally flipped images of herself, the mirroring recalls Valie Export’s Space Seeing – Space Hearing (1973-74). Accompanied by audio signal, an image of a woman flips back and forth symmetrically. In these pieces, Cortright and Murphy address the potential for infinite transformation of the self image by using consumer software.[8] However simple, these works are notable their irreverence and play that departs from historical conventions of feminist video art.

Comparisons could be drawn between the communication of intimacy and interiority in historical video and also web 1.0 net.art by women. Olia Lialina’s website, My Boyfriend Came Back From the War (1996), utilizes multiple frames with hypertextual links that require viewers to clickthrough to experience a disjunctive relationship with her hypothetical boyfriend after he returns from war.[9] On a similar formal vein of luring the viewer to click to unravel a fragmented narrative of image and text, Tina Laporta’s DISTANCE pairs glitching webcam pictures with poetically labeled hyperlinks to explore intimacy over the internet.[10] Meanwhile, Krystal South’s Overcoming Depression and Advancing to the Next Level combines affirmative statements with faded grey text that darken upon cursor movement over the text. Here the artist uses vernacular properties inherent to web-based text coding to convey ambivalent emotions.[11]

Cyberfeminist institutional critique

Cyberfeminists of the nineties sought to achieve equal technological footing to their male programming counterparts by ideologically infiltrating communication networks with sexually charged dissent. They posted their manifestos on mailing lists, message boards, and self-organized websites. “The Female Extension” (1997) arose as an intervention and response to the lack of female net artists, as well as the Hamburg Museum’s attempt to institutionalize net.art. Cornelia Sollfrank wrote a program to simulate over 200 international proposals to the Hamburg Art Museum in critique of a competitive call for submissions that treated “Internet as material and object”.[12] Sollfrank ‘s contribution occupied two-thirds of the submitted proposals that year. With the intention of creating disturbance in the submission system, she questioned the significance of even identifying the gender of the artist on the internet.

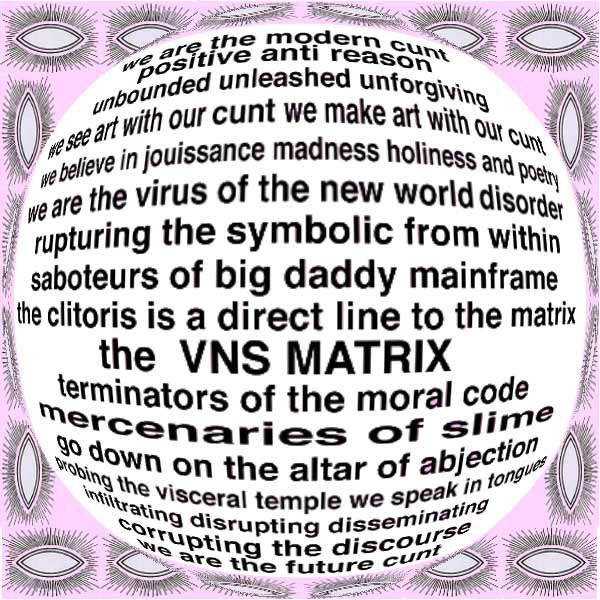

Unlike the constantly revisited feminist writings by Nochlin and Haraway, many radical cyberfeminist movements and manifestos (Old Boys Network, VNS Matrix, Ciberfeminist.org) are overlooked by academic publishing and eclipsed by Haraway’s theory. A flame war started when Ann de Haan posted ”The Vagina is the Boss of the Internet” (1996) on to nettime mailing list; list moderators asked users who wanted to discuss cyberfeminism to do so in feminist communities such as Old Boys Network.[13]

Amongst many online alter-personas, an equally voracious female profile was Netochka Nezvanova, an online intervention artist and software writer who possesses multiple personae. As the author of audio-visual mixing software Nato.0+55, which would run on Max, a visual programming software. Described as “the most feared woman on the internet” by Katharine Mieszowski, Nezvanova threatened to withhold distribution of the popular audio-visual mixing software when she was banned from a Cycling ‘74 software community mailing list.[14] Users have not determined whether the user behind her profile is biologically female, but she is nonetheless a prominent female entity in the software community. In arranged public appearances at award ceremonies, a different woman would always represent Netochka each time she agreed to appear in public, thus evading the need to reveal her true identity.

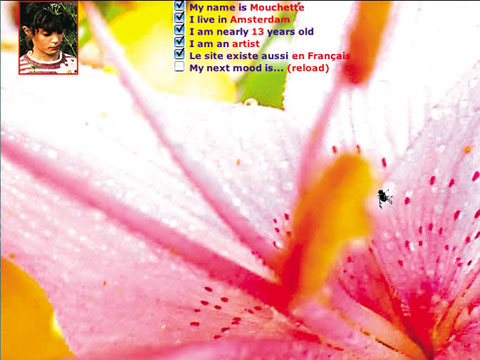

Similarly, Mouchette.org poses as the personal website of a thirteen year old girl, designed to titillate the curiosities of pedophiles which were a rising moral panic in the 90s.[15] The website’s author plays upon the narcissistic qualities of the interactive web 1.0 personal website. As the user navigates through the website by selecting radio buttons that ask them to make assumptions about the attention-seeking character of its author, closeups of feminine body parts (an ear, tied hair, a face with lips parted) appear, enlarged, across the background of each linked web page.

Performed Fluidities

In contrast to deliberatively provocative cyberfeminist statements, net art by women currently appears questionably complacent or complex. An unapologetically exhibitionist persona is Ariel Rebel. Filled with expletive status updates and gifs of dildos, glitter, and random online artifacts, her tumblr, ARIEL REBEL’S HAUNTED GRÄFENBERG SPOT is a mesh of porn, raunch culture and apathy that describes an indifferent mode to sexuality in light of the (re)sexualization of women after seventies feminism and MTV.[16] Although the persona has her own pornographic website (http://www.arielrebel.com), it is possible the user that runs these domains may not even be female-identified despite her virtual participation in an exhibition of net art at “Speed Show vol. 4: Super Niche” (2010).[17]

scandalishious (Ann Hirsch), caroline+heart, 2008.

Perhaps former successes of feminism allow women to feel less restrained in representations of themselves and the choices they make. Irony has become a formal device in feminist video that provides humor for audiences to cope with potential disappointment in the self and possible inequitable realities.[18] Other performing women are more overt in their gestures but ambiguous about their intent. Exploring the role of the famewhore or “cewebrity”, Ann Hirsch (scandalishious/Caroline Benton), boxxxy, and lonelygirl15 appropriate tropes of narcissism and solipsistic performance for the webcam to ambiguous effect.

Playing with stereotypes of the reality TV star, Hirsch created a website and YouTube profile around a camwhore persona (scandalishious) to seduce and titillate viewers with shameless dancing in her home. Much like boxxxy’s accelerated banter, the “pleasure of performance” is apparent in video. Performing ridiculousness with the logic of reclaiming stereotypes with hyperbole and humor, young women create video that both contradict and indulge stereotypes of femaleness and sensuality as opposed to the deadpan descriptions of one’s body and feelings in the seventies.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Ee4BOL-2yE&feature=player_embedded

lektroswirl (Vicky Gould), BEYONCE’S HALO WHILE I SLIT MY WRISTS, 2010.

The difference between the personal sentiments of the seventies feminist performance video and the webcam videos of the now is the increased use of humorous self-deprecation to regimes of representation in popular culture. While some revel in flagrantly queering gender boundaries, others reperform or resexualize gendered performances from pop culture. Meanwhile, in BEYONCE’S HALO WHILE I SLIT MY WRISTS (2010), Vicky Gould (lektroswirl on YouTube) applies lipstick to her face, gallivants to ”Halo” by Beyonce Knowles, and repeatedly motions to slit her wrists with a disposable razor.[19] Thus, Gould and Hirsch challenge contemporary tropes of the camgirl stereotype to unseat expectations of sexualized performance for the webcam.

Working with slick visual effects, electronic music and narrative, Sarah Weis and Arturo Cubacub uses common postproduction practices to render herself as a digital celebrity. In feature length film B-17, Weis’ character talks in frank high-pitched banter about her political escapades as a top-secret sex slave. Appearing in hyperfeminine costume and gaudy sets, Weis speaks of situations that are entirely probable as performance and always-fictive as situations, which nonetheless promote a sex-positive identity that internet audiences could find tolerant as entertainment.

Women Act, Men Appear

Criticism that their work is simply narcissistic forecloses opportunities to discuss the artist’s implication of themselves in a discourse of female representation in popular culture and user-generated material. In “Ways of Seeing”, John Berger reduces unilateral male-female gaze theory to the aphorism, “Men act, women appear.”[20] Paradoxically, his statement may also be inverted to complement my observation that women artists who are popular today are either performers or programmers. Like Petra Cortright, women performers are reveled, romanticized or exoticized,[21] but also actively present their bodies to gain visibility in an artmaking public. These self-as-subject performances are possible occasions for resistance and restructuring of agency surrounding relations of the male and female gaze.[22] Unfortunately, the very language they use to present themselves (i.e. high angle self-portraits and uptalking accents) still serve as entertainment for male audiences.

Transgression, remix, and empathy

Mike Goldby, The Body, 2010.

Feminist concerns are also expressed in remix and rearticulation of found media. Dara Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978) serially repeats processes of transformation and action to comment on the exaggerated body image of the Wonder Woman cartoon character. On the other hand, remix of familiar and mundane texts can also elicit fear, pathos and discomfort. Taking an empathetic position to the televised female subject. Mike Goldby’s looped, reversed and repeated closeup of Sarah Michelle Gellar’s face (Buffy conveys relatable emotions of ambivalence, concern and uncertainty in “The Body” (2010).[23]

Anita Sarkeesian, Too Many Dicks, 2010.

Female political remixers such as Elisa Kreisinger and Anita Sarkeesian (FeministFrequency.com) produce subtle and vernacular remixes of pop cultural content as queer narratives are omitted from the academic writing of remix history altogether. Calling herself a “pop culture pirate”, Kreisinger’s Queer Carrie series (2010) are five-minute remixed episodes of entire seasons of Sex in the City with heteronormative sentiments omitted. Inspired by Sloane’s Star Wars: Too Many Dicks, Sarkeesian created Video Games: Too Many Dicks remix video to satire the lyrics of an ironically sexist rap song by Flight of the Concords.[24] By creating a montage of first person shooter video-gaming footage from thirty-nine video games, she critiques the dominance of male characters and lack of female representation in these ultra-violent games.

Gendered critique in collaborations

While all artists that I have mentioned have been women so far, men were not absent from contributing to feminist commentary either. Collaboratively, Marina Abramovic and Ulay played gender-neutral roles and created performances that tested the body from a clinical perspective instead of emphasizing the biological differences. Their performance, Imponderabilia, was later reperformed in Second Life by Eva and Franco Mattes (of 0100101110101101.org, or 01.org), as Reenactment of Marina Abramović and Ulay’s Imponderabilia (2007).[25] Using the simulated space as a place for reperformance and social intervention (by blocking doorways as an artistic gesture), 01.org intervene in virtual space and challenge definitions of performance when they perform as disembodied avatars.

JODI and Irational.org created in websites that interrupted ones immersion with information delivery on the internet. From the 90s to 2005, JODI (Joan Heemskerk and Derk Paelsman) produced a series of vernacular interventions in the structural performance of video games, websites and internet browsers. Similarly, the jogging (Brad Troemel and Lauren Christiansen) had a tumblr that questioned the boundaries between art object and documentation. In Facebook-based interventions such as ASSEMBLY (2010) or READY OR NOT IT’S 2010 (2010) they intensified their use of media distribution platforms for institutional critique.[26] Meanwhile, Iain Ball and Emily Jones employ existing commercial aesthetics and found imagery to explore sustainable solutions to energy issues in E N E R G Y ⋮ P A N G E A (energypangea.org).

Apolitical Abstraction

Female-authored net art is not always fixated on the personal and the emotional. The work of Kari Altmann, Michelle Ceja and Jillian Kay Ross, and Sarah Ludy demonstrate their interests in the formal and the spatial. Altmann’s extensive production of 3D renderings, fictive interiors and found object installations defy categorization as any one artistic genre. Ross’ background in painting informs her abstract sensibilities and in the hyperreal renders of alreadymade sculpture in white gallery space. Ceja and Ross utilize the screen and the webpage as a space for representations of) installation with potentials for translation into physical exhibition. Untitled (2010) is looped stock footage of a wormhole that creates space with illusionism of animation and recession on a wall.[27]

Sarah Ludy, Otha, 2011.

Unlike Jonas’ work, the horizontal roll in Ludy’s videos (Otha (2011) and Transom (2011) reveal new architectural landscapes in reference to our windowed, mediated subjectivity. The impulse to describe infinite potential for unfixed representations of images in “digital space” is intensified by anne de vries’ forecast (2011). Movement through a structure of intersecting, gridded arrangements of cloud images are narrated by a robotic male voice that reads a text by Bertrand Russell.

The boring trafficking of conventions in net art irl

Online gallery systems are often as conservative as museums. The same way a regimented “contemporary” sensibilities of VVORK wind up in Reference or Preteen gallery, an adherence to software or new technologies on Vague Terrain may finds its curatorial interests manifested in shows at bitforms. Curatorial preferences for specific aesthetic principles (minimalism, gradients, vernacularism, found/3D objects) attract individuals with similar work to form online art communities.[28] As Brad Troemel noted in observing the induction of artists with online practices in real space, users with a preexisting online following are selected for enter gallery exhibitions.[29] Even though self-organized art distribution domains such as The State, jstchillin, and Computers Club feature a significant amount of internet art by women, these ground-up curatorial models only welcome women’s art when it looks like net art.[30]

While the potentials for self-curation of a gender-neutral or fluid persona are boundless in an online profile, arguments about technologically determined fluidity between genders do not resolve conventional myths attached to women and technology. Late curatorial initiatives that are represented as “feminist video” exhibitions appear to exhibit a reduced interest in accommodating a breadth of perspectives. “Modern Women: Single channel” at MoMA PS1 trumps modernism’s biggest feminist names-mostly those born in the forties-but does not offer many nuances to the feminist discourse of the seventies. What is represented as such a genre is usually a historicized narrative of political expression. However, “Reflections on the Electric Mirror: New Feminist Video” (2011) at the Brooklyn Museum differs from this formula. While accommodating for nuances of female expression and emotion, its curator, Lauren Ross, strives to differentiate these artists’ sentiments by describing them as “a new generation of feminist artists” that employ “varied approaches from humor to intense revelation”. However, it is unclear whether all artists in the program would self-identify as feminists; the only thread that connects all videos is the presence of the female subject.[31]

Myths and Statistics

Quantitative research carried out in the 1990s has found data supporting both arguments for and against gender differences that would affect women’s particiption in the IT field.[32] Gender role socialization may explain womens’ sense of diffidence towards success in computing. Pedagogical research has indicated that both boys and girls felt that computers were sex-typed for boys. While these research initiatives illuminate possible reasons why women may be discouraged to work in IT or new media, Rosalind Gill talks more specifically about discrepancy in will that younger workers will not confront.[33]

While my study is by no means a global survey, in large institutional exhibitions in the past year, museums have done little to level the gender distribution in media art exhibitions. A brief count of women artists who participated at recent internet-related exhibitions in major institutions show that programming from both self-organized and established venues have consistently included less female than male artists:

- Three out of fourteen artists were women at the first ever Speed Show (Berlin).

- Just under a third were invited to the first BYOB (NYC) at the Spencer Brownstone.

- Seven out of twenty-five artists were women in the first ever YouTube PLAY Biennale at the Guggenheim museum.

A notable exception to this imbalanced model was FREE at the New Museum, where almost half of the artists were women. While counting is a first step in noticing glaring differences in distribution of women artists in exhibition spaces, a thorough inquiry into the sociological and ethnographic contexts would be essential to begin increasing female artists’ inclusion and visibility in internet art.

Identifying a “cool factor” about the idealism and informality of new media careers in the 2000s, the work schedule of the new media artist creates latent sexism and racism that is embedded in the egalitarian culture of job flexibility.[34] In these environments, both male and female workers do not identify equity as a problem although women are awarded less projects, pay, or work in such workplaces. It appears that a dangerous mix of internalized postfeminism and meritocratic privilege underlines online culture as an always-only-equal environment on multiple grounds of race and gender due to the internet’s potential for free speech.[35]

Online, paradoxical assumptions of user racelessness and genderlessness in anonymous Anglophonic spaces further complicate discussions about technological access and identity.[36] We cannot remedy the situation by asking all unheard individuals to simply exercise identitarian or ideological “empowerment” through a use of media distribution platforms. A completely democratized system of art appreciation goes beyond the economies of “Like” and peer adoration on social networks. Such a system would validate the contestation of dominant and marginal interests through recognition of such voices through sharing, praise, critique, derision, and trolling.

Not all curators or museum directors are indifferent. Jerry Saltz’s open letter to the MoMA inspired an online protest from his Facebook followers, which led to a meeting with its director, Anne Temkin. In an article published after, she acknowledged the uneven distribution of women artists in the 4th and 5th floors (of 4% in 2009), but could not make any immediate changes to representing modernism despite long-term goals to include underappreciated artists that worked in the same period.[37]

Feminist or womanist curators and art historians attempt to justify the imbalance in cultural representation with examples of outstanding women who are already working in a particular genre.[38] The historical survey show, (such as “Modern Women: Single Channel” (2011) at the MoMA PS1) or the all-female show are two popular ways to present any all-female exhibition; it is “the” feminist or all-woman exhibition. These not only seek to temporarily illuminate the larger programming discrepancies through the celebration of female perspectives, without implementing decisive programming changes.[39]

Conclusion

This text presents a start on placing a critical lens on women artists’ representation in media art history and some problems with their position in exhibition contexts. While maintaining a web-based practice allows a greater audience to see the artwork, imbalances in numbers persist in exhibition spaces and the art world at large. My critique does not claim that there are no women internet artists or that there are none who are great enough to make a significant contribution to the fields of art and technology. There are, but they are not thoroughly recognized by their community and art institutions for their work alone. The onus is on emerging curators and artists–as content curators–to apply extra effort to research and include a diverse range of perspectives on internet art. This means consciously programming and including women whether or not they make work that fits within existing aesthetic sensibilities of what net art should look like.

If exhibition is a method of presenting feminist history and that history of contemporary practice in real space, scholars and arts administrators need to reconsider the aesthetic criteria that have led to a periodization of “feminist art” as a genre. Existing models of curating valorize effeminate or feminine forms of expression that may in fact validate old stereotypes as spectacle.. While I do not think it is problematic that the feminist art canon may embrace this, it cannot be all that is programmed formulaically. On a macro level these positions deter the actual feminist goal of achieving equal representation in exhibition spaces. To increase female presence in exhibition spaces arts administrators need to look beyond the femaleness or “feminism” in artwork, to consider its form and content in relation to the concept during the evaluation of “Great” art.

[1] I mean representation in terms of gallery representation, as well as media and artistic representations by women of themselves.

[2] This ongoing sexism that I am speaking of is most obviously represented by distribution and opportunities, but is not limited to the “pay issue” as feminists would call it. Later in this article I describe internalized forms of dismissal that may lead to a probable discrepancy in gender distribution.

[3] Evelin Stermitz. “Artfem.tv: Feminist artistic infiltration of a male net culture” Video Vortex Reader II, Edited by Geert Lovik and Rachel Somers Miles. 2011. Institute of Networked Cultures: Amsterdam.

[4] Linda Nochlin. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTnews January 1971: 22-39, 67-71. In 1971, Linda Nochlin argued that institutional constraints (educational and artistic) prevented women artists from achieving the levels of success compared to that of male artists in historical discourse.

[5] Steve Dietz, Why Have There Been No Great Net Artists?, CADRE on November 30, 1999.

http://www.walkerart.org/gallery9/webwalker/ww_042300_main.html

[6] Silvia Bovenschen. “Is there a feminine aesthetic?” Translated by Beth Weckmueller, Feminist Aesthetics, Edited by Gisela Ecker. 1985

[7] Brenna Murphy, yingyyangyhuman, 2011. http://www.flickr.com/photos/brennaaa/5472949494/

[8] Nicolas O’Brien. “Hyperjunk: net art out of the past”, Bad At Sports. April 12, 2011. http://badatsports.com/2011/hyperjunk-netart-out-of-the-past/

[9] Olia Lialina, My Boyfriend Came Back From the War. 1996. http://www.teleportacia.org/war/

[10] Tina Laporta. Distance, 1999, New Radio and Performing Arts, Inc., turbulence.org http://www.turbulence.org/Works/Distance/

[11] Krystal South, Overcoming Depression and Advancing to the Next Level, http://www.krystalsouth.com/depression.html

[12] Cornelia Solly, “The Female Extension”, 1997. http://artwarez.org/femext/content/femextEN.html

[13] Rachel Greene, “Web Work: A History of Internet Art”, ArtForum, May 2000, 166.

http://molodiez.org/net/rachel_netart.pdf

Ann de Haan, “The Vagina is the Boss on the Internet”, Net Time, June 16, 1997. http://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9706/msg00111.html

[14] Katharine Mieszkowski. “The most feared woman on the Internet”, Salon.com, 2002. http://dir.salon.com/story/tech/feature/2002/03/01/netochka/

[15] Mouchette. http://www.mouchette.org 1996.

Katya Bonnenfant. “Towards the anonymity of the artist” 2003. http://www.katya-bonnenfant.com/annesophie/comments04.html

[16] Rosalid Gill. “From Sexual Objectification to Sexual Subjectification: The Resexualisation of Women’s Bodies in the Media”, Mr. Zine. May 23, 2009. http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2009/gill230509.html

[17] jonCates. “tumblr fluidities, gender glitches + super niche haunts” Furtherfield, December 17, 2010. http://www.furtherfield.org/blog/joncates/tumblr-fluidities-gender-glitches-super-niche-haunts

[18] Hilary Robinson, “Activism in Practice” Feminism-art-theory: an anthology, 1968-2000, 2001. Blackwell Publishers Ltd: Oxford. 113.

[19] Lektroswirl. “BEYONCE’S HALO WHILE I SLIT MY WRISTS”, 2010.

[20] John Berger. Ways of Seeing. 1972. London, England, British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 45-64

[21] Domenico Quaranta. “It Takes Strength To Be Gentle and Kind”, April 20, 2010. http://domenicoquaranta.com/2010/04/petra-cortright/ Of Petra Cortright’s solo exhibition in 2010, Domenico Quaranta wrote ““Petra belongs to the first generation of digital natives… She lives online. Let’s spend half a day on Google searching for her and we will know almost everything…that she hates New York…her father died of Melanoma, that she had a wonderful love story and that she broke up. Her life is a continuous online performance…it’s about Petra Cortright. And it takes strength to be Petra Cortright.”

[22] Michele White. “Too close to see: men, women, and webcams” new media & society, 2003. SAGE Publications: London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi

[23] Mike Goldby, The Body, 2010. 2:58. Looped video. http://vimeo.com/20280129

[24] Anita Sarkeesian. Video Games: Too Many Dicks, 2010. http://youtu.be/4PJ0JPLg_-8

[25] Domenico Quaranta. “Eva and Franco Mattes, 0100101110101101.ORG Reenactment of Marina Abramovic and Ulay’s Imponderabilia“ http://www.reakt.org/imponderabilia/index.html 2007.

[26] jstchillin. “documentation of the events surrounding The Jogging’s Assembly project for JstChillin” jstchillin.org, 2010. http://jstchillin.org/jogging/

[27] Michelle Ceja, http://michelleceja.com/window3.html, 2010.

[28] Artie Vierkant, The Image Object Post Internet, 2010, 9.

[29]“ The distributional efficiency of artists publishing content online can very easily serve as an appendage of the art market. There is already a “minor league” feeder program in the making, where galleries and other institutions discover artists who are digitally popularized.“

Brad Troemel, The Minor League, cemetery, December 26, 2010.

[30] Furthermore, none of the “great” artists that he lists are women..

Rafael Rozendaal, “The Greatest Visual Artists”, New Rafael, 2010. http://www.newrafael.com/the-greatest-visual-artists/

[31] Brooklyn Museum. “Reflections on the Electric Mirror: New Feminist Video” 2010.

http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/new_feminist_video/

[32] Hope Morritt. Women and Computer Based Technologies. University Press of America: Lanham

[33] Gill, Rosalind Cool, creative and egalitarian? : exploring gender in project-based new media work in Europe [online]. London: LSE Research Online. 2002. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2446

[34] Gill, 24.

[35] Coco Fusco, “At Your Service: Latin Women In the Global Information Network”.The Bodies That Were Not Ours and Other Writings, London and New York: Routledge/iNIVA, 2001. http://www.artwomen.org/maquiladora/article-p2.htm

[36] Of identity and access to the internet, Coco Fusco discusses the predominant ways of viewing identity in relation to access on the internet. Arguing that real world assumptions of user whiteness and masculinity carrying over onto the internet in the forum domain as “non-race”, She calls feminine metaphors applied to computing and the internet “…a convenient masquerade of diversity for a milieu still overwhelmingly dominated by an extremely powerful… predominantly American male sector of world population. The abundance of descriptions of net communication as structurally anti-authoritarian, decentralized, “rhizomic,” open-ended… are effectively deterring attention from the centralized economic formations that sustain it…” Fusco, 2001.

[37] “The Feminist Evolution”, ArtNews, 2009. http://www.artnews.com/issues/article.asp?art_id=2800

[38] “The feminist’s first reaction is to swallow the bait…and attempt to answer the question as it is put: that is, to dig up examples of worthy or insufficiently appreciated women artists throughout history…” Nochlin, 90.

[39] In an interview with curator Derek Maniella revealed there was little criticality in the selection of female-authored works for ”Bitch Slap” (2010) at Thrush Holmes Empire–an exhibition that featured 28 Canadian women artists. He conceded to selecting artwork by women artists whose aesthetics he enjoyed. XBlog, XPACE, 2010. http://www.xpace.info/xblog/interview-with-derek-mainella-curator-of-bitch-slap-opening-nov-19-thrush-holmes-empire/

Comment

Could you maybe say on what page of her book Rachel Greene says that Ann de Haan was told to remove her text from Rhizome? If you did not get this information from her book, could you say where you got it from? It is quite a heavy accusation.

Hi Josephine,

Of my existing text, I am regretful to say that I have: 1) misinterpreted a quote by Rachel Greene 2) cited the wrong text that she wrote; I apologize. The following was what I meant to reference:

“While most participants prided themselves on their net.community’s relative enlightenment, cyberfeminism turned out to be an issue of interest to few. There was a flame war when Anne de Haan’s e-manifesto “The Vagina Is the Boss on the Internet” was posted to Nettime in June 1996. (The text is archived at http://www.rhizome.org/cgi/to.cgi?q=698.) Those who cared about cyberfeminism were told by list moderators to take the discussion elsewhere, to women’s platforms like the Old Boys Network (www.nettime.org/oldboys).”

Rachel Greene, “Web Work: A History of Internet Art”, ArtForum, May 2000. 166. http://molodiez.org/net/rachel_netart.pdf (page 5 of document)

In my multiple edits this has been skewed to what I have written in this text, and I realize that it is a misrepresentation of Greene’s observations. Accordingly, a thoughtful revision is underway for resubmission to this post, should the moderator allow.

Thank you for reading and drawing my attention to this!

[...] http://pooool.info/?p=278 [...]

[...] via Why Are There No Great Women Net Artists? « Pool. [...]

[...] Why Are There No Great Women Net Artists? [...]

[...] Why Are There No Great Women Net Artists? – Pool. Previous article [...]

Regarding performed fluidities, there is a reference to ariel rebel’s haunted grafenberg spot. having followed the blog for some time i believe it is run by a young man who vaguely looks like ariel pink and has a fascination with the ariel rebel persona of the pornography world, hence the amalgamation of the two for a blog title. Also when credited as participating in Speed Show, is noted as (identity not confirmed) on the webpage which signifies to me the play of co-opted identity in crediting ownership of the blog.