‘Unlike’: Forms of Refusal in Poetry on the Internet

By Samuel Riviere

xTx From Your Eyes

In his novel The Glass Bead Game (1943), Herman Hesse imagines a future in which art, music and literature as we understand them have ceased: culture is regarded as somehow ‘complete’, and the creation of new art is effectively forbidden. Instead, the players of the titular game draw on the vast repository of shared culture to construct a kind of meta discourse, answering each other’s ‘moves’ with referential improvisations. So a quote from Aristotle, for example, might be continued in a piece of mediaeval music in which some formal or thematic similarity is recognised. Hesse’s vision seems both charmingly antiquated, as it is not really interested in how technology would come to function as the storeroom of culture, but also prescient in its awareness that this horizon of unoriginality has come to be an anxiety and fixation for many twenty-first century writers and artists, a starting point for their own self-aware works of resistance and influence.

Perhaps the most obvious analogue for Hesse’s model is the rise of blogging culture, with its practice of primarily sharing rather than creating content, its infectious and mutating memes which breed increasingly referential combinations. There is a surface resemblance here, but we can go further and see this model expose how much creativity has a closer association with curatorial practice (as opposed to a Romantic notion of inspiration or genius) than it has ever liked to admit. Many poems we encounter can be quickly classified according to their precursors, their models and objectives – appearing almost like pre-existing formal contraptions for personal or imaginative content (the sourcing of which also has its well-tested methods). What interests me as someone who wants to read and write poems in late 2011 are the implications of poetry’s choice of continuing established traditions or of refusing them, in light of a new strand of internet-based poetry that has emerged over the past half-decade or so.

Historically, any significant shift in poetry has been a shift ‘down’ – to the demotic, the current vernacular as experienced by readers, who depending on their disposition will find it refreshing or exasperating in a poem. We can look most obviously in recent history perhaps to O’ Hara or the Beats, but the moment is replicated with poets like Coleridge (‘I would like to write poetry that affects not to be poetry’) or, going way back, to Dante’s Dolce Stil Nuovo (the ‘Sweet New Style’), as are, predictably, the reactions of the critics in office. Such a shift usually involves taking the cues for writing directly from life, rather than from the canon of poetry with which the poet may be attempting to ingratiate himself. Perhaps it’s mystifying how accepted and encouraged the latter approach is, when a surer tactic for writing innovative poetry is one of irreverence rather than imitation. Something in our awareness of poetry knows that its ‘job’ is not to slavishly follow established trends; we realise instinctively it is by its nature a subversive practice, connected with a kind of ideal spirit of honest perception, resistance and dissent. Probably this is partly why the people who are drawn to poetry are drawn to it in the first place. In the moments when it becomes culturally relevant or emblematic, poetry interrupts, derails, shifts; it does not reinforce. Yet the world one becomes familiar with if you aspire to write poems is quite different from anything these notions might suggest: a liberal establishment firmly in control of publishing channels, made up of bodies with decades of personal and professional investment in the type of poetry they write and write about. This would seem to explain the continuation in poetry of styles that have long outlived their reasonable lifespan. It’s not I think overstating it to say that an interruption or disregarding of tradition is simply not in any of these body’s interests. The normal defence one encounters here is that all poetry is ‘revolutionary’ or ‘experimental’, that publishers simply represent the foremost practitioners, and the change in register or tactics engendered by, for example, conceptual, flarf, or internet-based poetry, simply doesn’t offer enough in the way of rewards for the poetry reader. But it’s probably more accurate to say that it doesn’t chime with the perceived expectations of a ‘poetry reader’, who/what-ever that is in theory. When a magazine or publisher that survives almost entirely on arts funding is unable to generate enough interest to support its own programme, the efforts of many internet zines/publishing houses/poets, operating almost entirely outside that framework of support, yet receiving an enviable quantity of traffic and attention, should at least be acknowledged.

A glance at the traditions of publishing reveals that poetry only really exists to the extent there is technology available to produce it. It is entirely indebted to this technology for its presence in culture. Since printing became possible, poetry has been tied into an economic situation, and its presence as a material object is a direct result of this. People have never not needed money to write poetry (firstly in terms of time and education), and in publishing the schooling of a ‘market’ is largely dictated by the tastes of those in charge of the modes of production. The audience is in a real way a creation of these publishing channels, via printing and distribution technology. These channels absolutely dictate what constitutes the art form: rather than publishing models evolving as a convenient way to distribute already-existing literature, it is more the inverse: that literature evolves to meet the opportunities for capitalism presented by printing technology. Poetry has been regarded as a product for a long time, although it usually tries to distance itself from any formal similarity to such. Now superimpose this argument onto the present situation. The opportunity for creating and nourishing an audience for new poetry like this has never existed before.

Again it seems to be a case of what the ‘totally liquid’[2] audience/poet relationship enabled by the Internet exposes about traditional publishing models. It can appear that ‘gatekeeping’ authorities artificially perpetuate a tradition of poetry simply because it is easy to do so, and within that define a comfortable notion of ‘quality’, to the point that it results in a genuine repression of what kind of poetry is being written. It is not an exaggeration to say, in the UK at least, that aspiring poets not only learn to write in accordance with a broadly accepted style, but also share broadly accepted aims, in order to increase their chances of publication. This seems to be a very effective way of strangling an art form, ensuring a certain tradition is bought into by emerging writers and remains the dominant one.

The possibilities for reversing this situation afforded by the Internet are obvious and probably do not need restating. If we can say that in poetry the genuine tradition is anti-tradition, and that continual overthrowing of entrenched styles is desirable, then it is worth looking at exactly what form of interruption this new strand of poetry proliferating on the internet takes, and how valid it is in it positing itself as alternative writing.

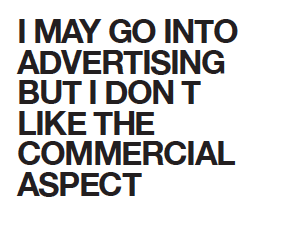

The Commercial Aspect

More than any other form of literature, poetry (even outside the type I’m describing here) has proved itself to be highly adaptable to an online environment. It would be naïve to assume that this doesn’t have something to do with the absence of economic benefits on offer in poetry publishing generally. Other writers are perhaps less used to the idea of making their work available for nothing, and are more reluctant to give it up to the vicissitudes of online culture, effectively relinquishing control over the poem’s availability and context. Poets seem more okay about embracing this. Poetry really has nothing to lose by abandoning established publishing methods, in doing so gaining freedom to multiply and attach itself to other ‘host’ art forms like videos or songs. This is connected in Internet poetry practice to a not un-ambivalent taking-on of tactics from marketing and advertising in order to promote and locate the work. Here we see a focusing-in on something the ‘poetry world’ (if such a thing can be said to exist) actively represses in its own representations. Poetry has become used to positioning itself as an ‘anti-commercial’ mode of culture, a somehow economically untainted art form. Poetry casts itself as almost the opposite of advertising, its ‘good twin’, and exhibits nothing but distaste for the tactics of branding or commodification given a good deal of attention by most other contemporary art forms. Of course, no poetry publisher would actively discourage people from buying its books, and would be delighted to sell more than the few thousand they can reasonably hope for – but in a way non-engagement with a commercial outlook, or lack or success there, does not exempt poetry publishing from having those concerns – it still operates with a structure of production and capital. If anything it is more obliged to consider them, as secretly (shamefully) they are at the heart of what it does. The lack of financial imperatives to remain within a traditional publishing format suggests that poetry is not only at liberty to define itself outside such structures, it is obliged to do so.

So maybe this poetry should be more like the best kind of advertising. A poet in many senses is already the same – ‘marketing ideas, marketing feelings, marketing a vision.’[4] Internet poetry practice zeros-in on such areas of anxiety and discomfort in its dominant other, and uses them for its own gains. It harnesses poetry’s own unpopularity against it. Tactics from branding and advertising are deployed to promote poetry zines and events, and inform the language and construction of the poems themselves. I would argue that these strategies of appropriation and internalisation of commercial culture orientate the poems both as antagonists of the dominant tradition (in poetry), and as self-aware artistic ‘brands’ within culture more generally, able to appeal to an online readership directly rather than just via a poetry audience and their disillusionment. This ambivalence, the simultaneous enjoyment of and anxiety about our complicity in mass culture, seems central to Internet practice, and is replicated on every level of its production.

The Brevity Thing

As blogging culture can highlight the curatorial choices at the root of writing, so the tropes of Internet poetry practice can reveal what is lazy or dishonest, or simply no longer appropriate in ‘normal’ poetry. As in other markets, ‘it is frustration with existing things that produces innovation.’[6]Poems that do well on the Internet seem to incorporate a few attributes, which appear as amplifications of the characteristics we might expect to find in an ‘ordinary’ poem.

The first of these is the appearance, the image-work of form which announces to readers that they are looking at a poem, albeit with a difference – brevity here is taken to a kind of extreme, and feels like an immediate statement about surface and expectation. We are startled or amused by the writing initially because it asks that we treat it as something labelled ‘poem’. Arguments that happened around conceptual art a century ago can be rehearsed here. We can also identify a flattening of tone, drollery, and an almost total absence of metaphor or ‘poetically’ constructed images. This refusal, the insistence on reduction and resistance, expresses fairly direct hostility to the values of preceding poetry or literary fiction. This is reinforced by subject matter – the poems’ reliance on references that exclude an older/uninitiated audience, just as younger poets are excluded from an ownership of history and told they have ‘nothing to write about’; the embracing or documenting of a culture of brand names and commodities that literary culture regards as ‘shallow’ and without interest for writers. Another impulse in the poems is the suddenly change of subject when things look like they’re getting too predictably in line with ‘poetic development’: non-sequiturs regularly intrude, and are anyway only a click away. It may be possible to draw this line of development alongside a generational rejection of the ‘affluence’ of older poetry, both in terms of its language and history, and as the actual recipient of financial support that seems unlikely to be extended to a descendent tradition. This rationale of ‘austerity’ in writing also mirrors the economic downturn, almost as a literal, self-inflicted condition of deprivation within the forms of poetry itself. These refusals result in striking, pared-back poems, often seemingly autobiographical (eschewing even imagination), in which the denial of metaphor or the reluctance to strain for poignancy in the way we might expect at a poem’s close, causes personal experience in fact to become more open, metaphorical, and grandly impersonal. This is echoed in the imagistic quality the text takes on when imagery is abandoned, and in the strategy of claiming techniques the establishment deems ‘not unsexy enough’[7] to be trusted in poetry. The result is a kind of seduction through renunciation, a desire felt through its obstacles, a fascination made obvious through the determined detachment of the writing. It ‘gains heat by looking cold’[8], ‘reminds us our laptops are warm’[9], and that not expressing emotion is not the same as not having feelings.

Touch my ass if you qualify

I have a friend who uses a lot of Internet dating sites, and we were talking about how confident he was in some of the ‘facts’ he was learning about his prospective dates. ‘It’s the internet,’ he said, ‘you can’t be sure of anything’.[11] This ambiguity inherent in language is something poets have always known about and exploited as a kind of ‘negative capability’[12], but awareness of this seems intensified online to the point of a fixation. Constant ambivalence, anxiety about how ‘serious’ someone intends to be, is experienced through the continuous use of qualifiers, non-sequiturs and other non-literary traits, such as misspellings and scare quotes. The internet is a ‘mall-like’ environment, an ‘infinite interior’[13], and along with the unquivering light, its discourse is its backdrop – a tone generated to compensate for a particular unease, the combination of immediacy and distance we experience in online conversation. In a way, communication here always freights itself with the possibility of alternative readings, purely as a method of making interaction more flexible and less formal than it might be. Online discourse opts for deferral every time, and its poetry acts out the same reluctance to commit to anything completely, to demonstrate certainty about one’s knowledge or opinions. Undermining every statement with excessive qualifiers, abruptly switching scene or subject, presenting received phrases as quotes, are all ways of saying ‘These words don’t stand for me’[14]. This position of continual deferral coincides with a media backdrop which emphasises multiple-ness and relativity, and deploys irony reflexively in aid of its objectives – we can’t ever know what the ‘right’ action is, on the level of a society, so being resolutely uncertain can be understood as a desperate effort to occupy a sincere position. ‘Uncertainty is the only emotion that does not deceive’[15], so the only time one can be sure of being sincere is while demonstrating ambivalence. Ambivalence is also a state of potential – for movement, action, meaning, or identification. The poems’ reluctance to settle on a meaning or approach a larger type of sense can be read as an attempt to be as honest as it’s possible to be while knowing what we know.

Next-level Authorship

If every blog is a confusing portrait

Of some anxious geek, then how can a poem

Not be confessional, similar to Bruce Lee

In a house of mirrors?[16]

The ideal of sincerity is centred in these poems through their admission that selection and negation are the fundamental binary in language. Their assertion is their flat refusal to be emotionally directive, to attempt to manipulate the reader’s feelings or attachments, and instead to provide the coordinates of experience without the cues for interpretation. Combined with the selection of what is ostensibly autobiographical material, this challenges a reader to reconcile the poems’ prioritising of surface with their own ‘depth’; the apparent comfort with transience with their own desire for continuity. Although these texts obsessively take note of the various signs, brand names and many other instances of commodified language that prompt us to incorporate their meanings into our lives (and contribute ours to theirs), we are confronted in these reductions with what is perhaps the least materialistic writing possible. The choices made in the writing seem to infer a shared set of assumptions, a hierarchy of knowledge tilted towards the immediate experience rather than the layerings of history or memory. The intercepted commands from advertising and other media are the most significant intrusions into our experience of narrative, directing the paths we take through our cities and online. In a strange way, I am reminded of the ‘guides for blind’ you can opt to have playing during a film, which announce flat descriptions of the characters’ behaviour without any glimpse of their appearances or into their subjective interiors, and force us to in some way inhabit or surround that blank at the centre of another person. Here we can sense this work’s questioning of poetry’s other great taboo or ‘blind spot’ – that of informing a poem with biography.

Online, a poet assumes the role of publisher and ‘author’ of their public image. When any name can yield a wealth of information, these poets seem to encourage a conflation of their creative output with extra-literary content. A central project such as a blog might be the main work, with poems and other texts incorporated into an image-complex orientated around the personality of the poet. The catch here of course is that there is ‘no’ personality. All we have access to is a series of texts attributed to the same individual. We ‘see’ the poet, but via a confusion of angled surfaces. The line between what can be considered extra-textual and what is creative work ‘proper’ no longer seems relevant: all information asks to be considered at the same distance. In a way this strikes at the heart of the practice of poetry reading. When I began studying poems the first thing you learnt was to view the text as a kind of sovereign object, existing in a vacuum or Matrix-like white space. No-one who reads poems can doubt that this approach does allow for more involved or perceptive readings than those from more journalistic angles, dragging in details from the poet’s personal history to provide a ‘definitive’ interpretation. Internet poetry practice asks something like the opposite, though, and seems to take Barthes’ well-known point with all its implications. This second-level awareness and control of the poet’s presence beyond their poems, incorporating biography, blogging, social networking and so on, demands that we read all of this content in terms of the poems and vice versa, and challenges the difference. The image of the poet that begins to emerge here is one quite different from what we might ordinarily imagine: a curatorial figure inscribing their presence through their social involvement with language; in a sense treating themselves as text, and inversely accepting that these choices continually restructure the self. But the poet’s personality as image-complex would not suffice without the counterpart of the poems themselves. Going back to the analogy of advertising, the extra-literary text here functions as advertisement for the poems, which function as advertisements for the author-brand: both are secondary content for a final product that is endlessly deferred, and that need never materialise. The commodification on display here has no final agreed value or meaning, as it is used to sell ‘products’ (poems) which are hard to place value on and are not ’sold’ online in the traditional sense. The ‘price’ and the ’product’ are the viewer’s time and engagement with the work. The destination of productivity in capitalism is always profit, so to deploy its most avid and remorseless tactics in the aid of poems implies both an uneasy celebration of commodification’s seductive but ultimately mortifying processes, and a critique of the same through applying such values to what is in practical terms an economically valueless object: a poem. This practice is, in the absence of fiscal results, a nihilistic act of aggression towards the ‘sanctity’ of poetry, an anti-commercial statement of capitalist impotence, and conversely, an earnest attempt to ‘popularise’ poetry using tested methods.

Of course, there is another level of reality occurring here: the vast economic infrastructure on which the Internet is built, and many of these works do celebrate unquestioningly the opportunities afforded by social networking etc. But there is nearly always an attendant anxiety, an awareness of an individual as a conduit for capital, via Google ads for example, and a suspicion of why these companies are so keen for us to interact with them. There is also a sense of experienced fragility of the self in this environment, its paralysis, its uncomfortable visibility in language, the sort of claustrophobic stupor arising from the same cycle of scenes that appear endlessly on our monitors. It’s probably easier to be pessimistic about the scale of this participation and investment in online culture, but at the same time user/brand relationships are still being defined, and seem fluid enough to allow certain opportunities. The final value of these encounters is yet to be determined, and with effort could become ultimately humanising, and, as has been seen over the past few years, include methods of disrupting many kinds of dominant cultural narrative. The power and innovation of this poetry stems from this moment of ambivalence occurring on all levels of its practice – it feels something like a pause, a hesitation hanging in the air after a voice is interrupted.

Interrupting Yrslef

because I prayed

this word:

I want [17]

The world of The Glass Bead Game is one in which innovation is limited to the tracing of traditions with total fidelity their development and context. There are rigorous criteria which must be gone through to admit additional subjects to the game’s repository of culture. The parallel I’m looking for here is with the type of interruption that Internet poetry practice makes in its larger tradition. The deliberate turning away from history and memory, the territories that literature normally wishes to claim, ensures it freedom from any obligation to that narrative: it owes nothing to that set of priorities. It insists instead on the authority of the personal, the immediate, intensely subjective experiences that are shared by millions.

Hesse’s society is also one in which the ‘cult of personality’ has been relegated to history – players are not known by their biographies or even their names, but by the record of their contribution to the game. Internet writing insists on personality to entertain a wider textual project, a more encompassing writing practice – it takes control of an audience by anticipating their interpretation, and ‘reconstitutes’ their expectations accordingly. To publish poems on the Internet means being alert to the paradox of ownership that a ‘text artist’ negotiates. A poem is not like other types of artwork, especially in the post-internet world. A poem is never really the original object. It is a construction in language, infinitely and easily reproducible. It cannot be fetishised in the way a piece of conceptual art can be, or ascribed an abstract financial value. Its loyalties are in some ways older and truer than that.

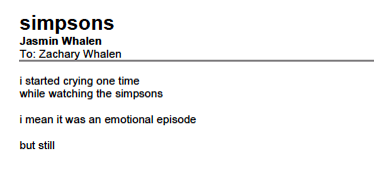

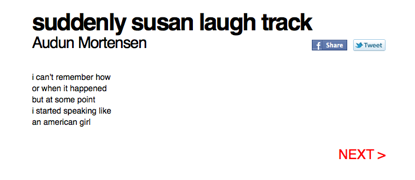

The world of The Glass Bead Game is also an entirely male world: in my edition of the book, no female presence is even mentioned until page 76. This is perhaps the most tendentious part of my argument, but if we are to ‘imagine an alternative lineage’[18] for this practice, it makes sense to look briefly at the birth of the lyric poem. Anne Carson has written convincingly about Sappho’s lyrics as the origin of not only lyric poems as we know them, but as the remnant of emergent literate culture, the language first used to articulate something absent. In ‘fragment 31′, Sappho speaks from an occluded position, observing the woman she desires talking to a man, who does not speak. The poem’s impetus is this sense of being barred from the desired thing: the poem exists to cover that distance imaginatively. The interesting thing about Sappho’s femininity here is the way her prototype for the articulation of desire has been taken on many times since, mainly by male poets, across the intervening centuries. In a sense Sappho is always ‘quoted’ in these poems of distance and longing – we feel her interruption to the wider male dialogues of desire and ownership. The type of linguistic interruption in Internet writing also seems gendered: characterised by sassy rebuttal, the progenitor of which is a kind of brutally enhanced high school dialect: ‘I started speaking like an american girl’. Perhaps the sympathy between these short fragments that have survived thousands of years, and new pieces of text being typed into word processors is not only an aesthetic one: they both encapsulate the same sense of intermittency and immediacy, of being a person only so long as you desire something and speak, before falling back into silence.

Poetry always fronts a lack. What’s written is assumed to be about something missing, or there would be no reason for writing it. Sometimes what’s missing is simply closeness to a person. Writing creates a field between wishing and acting, a place to act out and modify the fantasies that structure the way we experience our lives. These fantasies regulate and distribute desire, including the desire for knowledge. But what if this fantasy is precisely of life without its fantasised dimension? A world of actions and thoughts terminally divorced from each other, without the knowledge that draws them together. This is a vision that admits it requires the presence of a human to experience the links between actions and thought. This enforced absence in much Internet literature, of the feelings that connect actions and people, is the manifestation of a ‘third thing’, the obstacle between us and the other, in this case between poet and reader. We can know Sappho’s work (what remains), but we can’t know her, just as we can’t know a person from the selected fragments of language we hear or read from them. This poetry advertises lack, and celebrates the means we have to try and compensate for it, even if it knows it can never cover the deficit.

One of these means is the invitation to read ‘upwards’, to the poet’s biography, their life, as if the emotive material absent in the text could find its missing part there. This works almost magnetically, and indeed can be engineered by the poet, who can choose to what extent they furnish their pieces with extra-literary text. They can even engineer a further refusal. Take the work of Frank Hinton, who seems like an appropriate exit point for this piece:

This publication features first person speakers that alternate gender between pieces, and omits the author’s gender from the biography. This occluded spot of information is probably enough to send some to Google, where the lack within the text is replicated, with interviews attributed sometimes to a man, sometimes to a woman named Frank, which is ‘not her real name’. ‘Is Frank Hinton fucking with me?’[20]might be the first response, but this should be replaced with what this reveals about our involvement in the texts: the way we always seek meaning elsewhere to negotiate this obstacle, and that reading is precisely this act of reaching. The name of the author of the above text is a kind of puppet, a glove: ‘I let someone else put their fingers up there and type’, which signals a lack however you look at it.

Whether these refusals are as extreme a renunciation as repressing poetry altogether, or manifested in the exclusion of emotion, the obvious lack present in these texts generally works to attract other kinds of text or experience to fill in for its absence. Because we don’t know what precisely is absent, we can’t assign it a single meaning, just as the unconsummated status of both commercialisation and poetry means we cannot assign intention to either objective. Inevitably this work countenances failure – but it does so generously, courageously even, appreciating its high-risk strategy and the odds against it. If we find the violence of its refusals and evasions moving, this is surely partly in the recognition of our own impulses and doubts there, in its desperation to connect, knowing simultaneously that it is beyond anyone’s means to ensure this.

There is something both extremely personal and totally universal in poems that enact this moment of uncertainty: we see ourselves in their missing part, in their loneliness. The obstacle between us and meaning is somehow an internal deficit as well. These moments in language that we are able to inhabit are beyond any single identity. Perhaps what this strand of poetry is really engaged with is creating such sites under contemporary conditions, united by a rejection of any type of speech that rings false through its very assertiveness. What unites participants is this shared unfixedness, they are part of a kind of interchangeability. In terms of a tradition in poetry, if we can imagine a disruption to the liberal male narrative of refinement and smoothness, our own expectations of how meanings should be ordered and prioritised, Frank Hinton is basically that fantasy. And if the spirit of the work persists, avoiding compliance with what we expect from poems, generating its own appreciation and audience, it may arrive at forms we find it increasingly hard to call poetry, in which case its point might be to ask what it is we’re looking at.

[1] http://www.pangurbanparty.com/

[2] Jon Leon http://www.thehothole.com/forever/rightnow.html

[3] http://www.steveroggenbuck.com/

[4] Adrian Urmanov http://www.maintenant.co.uk/

[5] http://zacharywhalen.blogspot.com/

[6] Charles Bernstein

[7] Dan Hoy http://www.montevidayo.com/?p=793

[8] George Szirtes http://georgeszirtes.blogspot.com/2011/09/sincere-austerities-3b.html

[9] Sofia Leiby http://pooool.info/uncategorized/i-am-such-a-failure-poetry-on-around-and-about-the-internet/

[10] http://www.audunmortensen.com/

[11] Edmund Gillingwater https://twitter.com/#!/EGillingwater

[12] John Keats http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_capability

[13] Blaise Larmee http://blaiselarmee.com/texts/

[14] Megan Boyle http://matadornetwork.com/notebook/interview-with-megan-boyles-poetry/

[15] Slavoj Zizek http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DhDuYfZa5dE

[16] Linh Dinh http://wwwwsonneteighteencom.blogspot.com/

[17] Sappho, transl. Anne Carson http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/samples/random042/2001050247.html

[18] Charles Bernstein

[19] http://safetythirdenterprises.com/

[20] Stephen Tully Dierks http://htmlgiant.com/reviews/there-are-no-entities-only-processes-re-frank-hintons-i-dont-respect-female-expression/

Comment

Issues

- November 2011 (6)

- October 2011 (5)

- September 2011 (5)

- August 2011 (10)

- July 2011 (10)

- June 2011 (10)

Recommended reading

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Avec Bonus Sans Depot

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Online Casino Canada

- Trusted Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Sites UK Only

- UK Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Best Online Casinos UK

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Betting Sites That Are Not On Gamstop

- Migliori Casino Online

- Top 10 Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Meilleur Site Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino Online Esteri

- Paris Sportif Ufc

- 仮想通貨 カジノ

- Top Casino En Ligne

- 코인카지노 사이트

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Français

- Siti Scommesse Non Aams Bonus Senza Deposito

- Meilleurs Casino En Ligne

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Site De Casino En Ligne