05.04.12

Troll Culture: A Conversation with Stefan Krappitz

Finding out about Stefan Krappitz’s book Troll Culture, felt like an odd coincidence, as I was in the process of investigating the possible connections between the art of trolling and trolling as an artistic practice. I stumbled upon Olia Lialina’s link one day while looking up social hacking strategies and pre-2.0 trolls that had to adapt their tactics to a new social networking reality. I knew that trolls were really marginalized by the media (a recent action by the BBC underscores this tendency) and was curious to discover alternatives approaches to this premise, approaches that were opposed to the view of trolls being these sinister basement dwellers planting traps on different online platforms while lurking in shadowy spaces waiting for innocent victims. Such a surprisingly narrow understandings of troll culture paints, what is actually a very fluid and adaptive practice-into a modern day portrait of a gargoyle in front of the computer screen. As I was reading Krappitz’s book, the alternative understanding of troll culture I was looking for began to present itself. What I read wasn’t a one sided affair either: it both exemplified the awesome and fun parts of trolling while criticizing actions that picked on defenseless victims or that used insults as vicious weapons.

I thought about this for a while and started drawing lines between the Anonymous movement, artistic practices and the trolling strategies that Troll Culture touched upon. Some of these lines were dotted, some broke off somewhere in-between, while others connected seemingly unrelated actions and critical positions. I felt the need to find out more about these possible connections and interactions so I sent Stefan some questions I had regarding his book. Below is our conversation.

Matei Sâmihăian: The first obvious question is why did you choose to concentrate on this subject for your book? What did you find so interesting about trolling?

Stefan Krappitz: At first, I was really influenced by Olia Lialina’s and Dragan Espenschied’s work on Internet amateur culture. Their way of seeing the good things in Geocities or Comic Sans MS was and still is very inspiring to me. Trolling was always something that fascinated me, because it can be so much fun to use an infrastructure in a different way than it was thought of (Tobias Leingruber i.e. FFFFF.AT calls this “skating the web”. Also an influence). I’m not claiming to be a supreme expert in trolling, but I loved to troll Internet forums or chat rooms with my friends in the late 90s and early 00s. When I got aware of 4chan and Encyclopedia Dramatica, I was fascinated by the creative methods some of the trolls developed there.

At first, my topic was 4chan, Anonymous and its troll culture, but since the approval of the topic, Cole Stryker announced a book entitled Epic win for Anonymous and the Anonymous movement grew somewhat bigger than troll culture. I neither wanted to rewrite Strykers book (since he had already written it very well), nor did I want to write on the political aspects of Anonymous protests. I was more interested in the troll culture part of the topic, so I narrowed it all down a bit.

At the same time, I really saw a strikingly negative consensus in media coverage about trolls. Even interesting books like Stryker’s describe trolls as “bored teenagers”. This is not fair, in my opinion!

Another thing that bothered me was the lack of literature on trolling.

For example, most of the few cited texts on Wikipedia are from the 90’s and belong to books that don’t even concentrate on trolling (Judith Donath writes about identity and deception on the Usenet, and Julian Dibbell writes about a griefer in an early text based online community called Lambda MOO).

My motivation was to prove that trolling can be fun. I wanted to show the phenomenon of trolling as something worth researching. It was also very important to me to show the whole thing from a rather neutral point of view by describing both “how to be a troll” and “how to defend from trolls”.

MS: Given the multiple forms of action you interpret as trolling (the Socrates example in the book), what do you think the difference is between trolling and culture hacking? Is it the lulz?

SK: Yes, the lulz is a very important part of it.

Lulz is by the way an often misinterpreted word. It can’t be used as a synonym to lols. Lulz includes some form of Schadenfreude.

MS: Isn’t that too much of an insider joke that rings a bell only to a chosen few?

SK: It lies in the nature of trolling, that not everybody, especially not the victim, knows what is happening. However, if more people do know about the joke, the overall lulz created by it is increased. Often, it is enough to reveal the joke afterwards. Think of David Thorne, who created a fake profile of a young girl on Facebook. This girl “forgot” to set her birthday party to private and ten thousands of users joined the Facebook page for the party all the while Mr. Thorne was selling t-shirts to the “best party ever”. Politicians and journalists all of a sudden started to discuss this Facebook party. After all the buzz settled down, David Thorne revealed the true story. If he hadn’t, this would have remained just some poor girl’s crashed birthday party, but by revealing the whole story, many lulz have been had afterwards with all the buzz that was created. All of this made me think,“Well played, Mr. Thorne.”

Sometimes however, being one of the few in on the joke is just the best thing of trolling. There is a good example from Germany. After a school gun rampage, politicians blamed violent video games like Counter-Strike or aggressive music like Slipknot for it. Apart from the tragedy that is connected with a school rampage, reactions from politicians and the media enraged the younger generation. When there was a school shooting in Winnenden, a random troll from krautchan (German 4chan) faked a suicide note from the shooter as a krautchan forum post. The German media somehow got ahold of this and criticized the whole Internet, because this guy had foretold his doings before online only nobody took him seriously before. The message itself was really digging up all these stereotypes and it got so far that the interior minister of Baden-Württemberg read the message, which was full of hidden German chanspeak (grillen gehen = go to a barbecue = commit suicide or Bernd = The name for the German Anonymous), live on every television station. Getting a leading politician of your state to read a fake message was definitely lulzy for the few that recognized its real source by the German chanspeak.

As it was revealed to be fake, the whole German media was put in an embarrassing situation for not even checking the source of the message.

MS: To me it seems more like a micro-culture - a trolling-specific one (game grifeing, 4chan raids etc.) - that’s only relevant to specific cases or actions. Isn’t there a danger to pinning down these very fluid strategies into a genre or a culture or to analyze them in an anthropological manner?

SK: You are absolutely right. This is why I used a relatively wide definition.

As I wrote in the introduction to the chapter, “Be a Troll” those methods change all the time. Trolling is about always finding new ways to act differently from what people would expect. This is also the creative aspect that I like the most about trolling. Infiltrating a system, like Tracky Birthday called it. When writing about trolling techniques, all you can and should be doing is making exemplary “screenshots”. Fitting these liquid forms into fixed traditional academic categories is not the right thing here. It’s not about the current techniques, but about the creative methods in generating new ones. For this, I give various examples in my book and explain how they work, in order for you to develop them further.

Think of a feminist community. If you would create an account just to write something like “Why are you on the Internet? Get back to the kitchen and make me a sammich!”, the only thing likely to happen is that your account and the post getting deleted. So many people have tried this before, that by now, the message has become pure noise to a target group. To be a successful troll you have to come up with something new.

MS: After recently seeing a video about a Welsh troll that was defaced by the BBC, I found myself lurking on different channels to see reactions to the video. While in your book you criticize these simple minded trolling strategies, what is your reaction to the replays and comments in relation to the way the BBC handled the whole issue? Is there something at stake here?

SK: This is a really difficult question, because you can’t generalize. In this case, I really don’t like the way the BBC is approaching the troll. He had no real chance. The sole purpose of the interview on the street was to make him look like a stupid sociopath. It could have been really interesting to find out about his motivations, but obviously the BBC was not interested in this. If you want to find out about a trolls motivation, you shouldn’t be so extremely judgemental, but rather respect them, even if the troll IS a sociopath.

On the other hand, this guy is not a good troll at all. While I found it extremely difficult and overbearing to point out the border between morally bad and good trolling, I tried to give it some direction. Just writing insults on a memorial page on Facebook is as creative as randomly punching a twelve year old schoolgirl in the face. Creativity is somehow an indicator of quality here.

There is however some kind of guideline to trolling in my book.

Julian Dibbell wrote:

“the Internet is serious business’ means exactly the opposite of what it says. It encodes two truths held as self-evident by Goons and /b/tards alike — that nothing on the Internet is so serious it can’t be laughed at, and that nothing is so laughable as people who think otherwise.”

While there is nothing more ridiculous than people taking certain things on the Internet too serious, it is quite normal to care about your real-life. When I’m using the term real-life, please note that it does not necessarily exclude online activities. Life on the Internet is real too and sometimes it matters and other times it doesn’t. Deciding where to draw the border is one of the most important things when it comes to identity on the Internet. Ruining this real-life and laughing about people taking it seriously is, contradictory to mocking people who are taking weird aspects of online life too serious, the lamest variation of trolling.

The comments on the video are interesting, in that they somewhat resemble the unfiltered view of the users. While some are just negative about trolling, others go in the direction of “trolling can be fun, but this guy is not even a real troll for he is just randomly insulting people.”

This is also somewhat similar to my opinion.

Trolls should judge their own actions and try to be as creative as possible and to create maximum lulz! By just hurting people that are legitimately grieving for their lost ones, you are neither creative, nor are you creating lulz for anybody else than yourself.

After all, this video shows the bad reputation of trolling in traditional media versus the more sophisticated reputation of trolling among the users (comments). I really like this confrontation.

MS: In your view trolling as a cultural phenomenon is closely linked to anonymity. Do you feel like trolling shouldn’t happen on social networks like Facebook or Google+ or that it should be done in a different way? I’m thinking that you’ll probably feel more “entitled” to troll a friend rather than a stranger, but then where’s the lulz…

SK: While I link trolling to anonymity, I also do link it to identity or pseudonymity. At first this sounds conflicting, but at a closer look, it is not. Both anonymity and identity are listed as techniques against trolling in different sources I reviewed and it perfectly makes sense.

The idea of trolling linked to anonymity is somehow obvious:

If everybody is anonymous, you cannot be made accountable for your actions. Your true self remains hidden and this makes it really hard for you to be confronted with your own actions.

On the Internet, this is known as John Gabriels Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory or, in psychology, as the online disinhibition effect.

On the other hand, people are more likely to expect trolling in anonymous environments. That’s why 4chan has the rule “Pics or it didn’t happen!”. Timestamping is also a necessary technique to get credibility in anonymous environments.

In addition, it is really difficult to pick a target and see the effects of your actions as a troll when everybody is anonymous.

Identity is often cited as a good technique to prevent trolling, which is not completely true. While trolling on Facebook or Google+ is harder than in anonymous environments, results can be a lot more rewarding.

There are several reasons for this: First of all, people on Facebook are normally not expecting trolls as their conversational partner. Second, it is really easy to pick out a target. Third, the troll sees the impact of its actions. The only difficulty in those identity-based environments is to fake a reasonable identity. I’ve seen threads on 4chan, where troll accounts on Facebook build networks by befriending each other. A fake account with 78 friends is much more believable than one with zero friends.

An example on how to troll your friend on Facebook would be (your friend needs to be in the same room with his computer) to sneak to his computer when he is away to the bathroom or gone for a smoke, and set the default privacy options on his Facebook to “visible just for yourself”. Since he likely doesn’t expect this, he will continue posting stuff and wonder why nobody likes or comments on his posts. There are lots of good ways to troll on Facebook and Google+. David Thorne used Facebook too when he set up that fake public Facebook party. Nobody expected the young girl to be a fake profile of a troll. That way the whole action could work.

MS: Internet serious business? Gabriela Coleman sees the lulz as a departure point towards a more socially engaging way of political activism. What’s your take on the subject?

SK: I think that the border between activism and trolling is really blurry.

While some forms of protest, like hacking the website of Paypal are easier to classify as activism (they didn’t do it for the lulz primarily), others are classy examples for trolling. Remember operation slickpubes?

A guy from NYC collected the pubes and toenails of other members of Anonymous and covered himself in Vaseline and said toenails and pubes. He then ran into a Scientology building and smeared the pubes and toenails all over the place. Since he was also covered in Vaseline, he was so slippery that the security couldn’t grab him. Other members of Anonymous filmed it and uploaded the footage to YouTube to spread the lulz.

In the actions of Anonymous, both collective trolling and activism are really close and most of the times include each other.

YouTube PornDay, for example, was an action in which Anonymous protested against YouTube’s policies by flooding it with porn. The aspect of lulz is bigger than the activist component, which classifies the action as trolling.

MS: Art as trolling or the art of trolling?

Some artists employ trolling strategies within their work, I’m thinking of jodi’s thumbing youtube project, the Ten Tenten facebook one, but also of Tracky Birthday or Costant Dullaart promoting his IRL exhibition by trolling almost everyone in his Facebook list. There’s certainly a sort of difference here by means of targets and lulz audiences. How do you see this artistic trend in relation to troll culture?

SK: Trolling is an art!

I see great potential in trolling as an art. One example, which is also covered in my book, is Dennis Knopf, aka. Tracky Birthday’s Bootyclipse, where he downloaded bootyshaking videos from YouTube, removed the bootyshaking and re-uploaded them to YouTube under the exact same name with the same tags as the original.

He also trolled everybody by setting up a fake NY-Times page (that is down now), containing an interview with himself, when he launched his new album called “New Album”.

Another great troll/artist is Dragan Espenschied who made a collaboration with Aram Bartholl when he spread the fake news, that Google Streetview now costs money in Germany because otherwise Google couldn’t afford the costs of everybody requesting to get their house blurred out (that is an actual problem with the people here in Germany). He attached a link to a fake Streetview page that required payment to browse the content. Although the input fields for the payment information were dummies, the site got marked as a phishing site very quickly and disappeared, but the idea behind this action is really nice.

Since trolling is about creative play with people’s expectations or about infiltrating systems, I see a big connection to art!

MS: Do you have some good examples of RL trolling?

SK: Of course! RL trolling can be a lot of fun!

I remember trolling Aram Bartholl once, when he held a lecture at Merz Academy and went outside to get a cup of coffee. I ran forward to his notebook and plugged in the receiver for my wireless mouse to the back of his notebook (one of those that stand out just 3 millimeters when plugged in). As he came back and showed us something, I could safely open any YouTube video while he was talking to us with the projection in the back. Even as he realized, that something is wrong, he still didn’t know how it worked!

Another more artistic action, two fellow students and me came up with (also during the workshop with Aram Bartholl) was infiltrating Media Markt (German version of BestBuy). We printed out pictures and put them on USB-Sticks and went into the Media Markt. Then we photographed the pictures with the digital cameras they had on display and used their displays as our canvas. Then we went on to the computers and set the pictures from our USB-Stick as wallpapers on the PC’s and Notebooks.

We started some kind of exhibition like this. Sadly, while the employees had no idea what we were doing with the USB-Sticks, they did see our camera very quickly and threatened to throw us out of the shop immediately if we go on filming. Therefore, the documentation sucks.

Not that artistic but still really nice is sticking small trollface stickers over the sensors of optical mice, or making candy-apples with onions instead of apples, or somehow getting people to visit shock sites like lemonparty.org (don’t go there unless you want to see three elderly men doing “things.”)

Tracky Birthday came up with a nice idea to troll party people when I talked to him about my book. Just take an existing party and design new flyers for it. The fake flyers, however, state that it is a pyjamas party or some bad-taste party. Print them at some online discount printer and lay them out everywhere. Then turn up at the party to see the people going to a regular party in pyjamas.

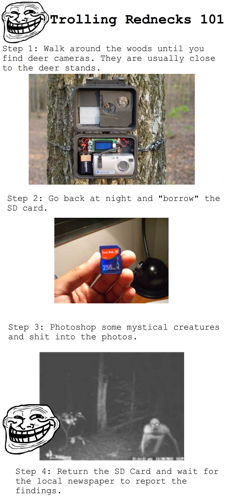

Another great idea, I found somewhere on the Internet involves those deer-cameras that automatically take pictures when something in front of them moves. All you have to do is open the box and borrow the SD-card. Then, at home, open one of the pictures on the card and photoshop some kind of monster into it. Then put the card back into the camera and wait for the television to broadcast a story about the monster in the woods.

Again, all this works because you would not expect someone to do this.

MS: Are you a troll?

SK: Aren’t we all trolls sometimes?

Here is a record of my most epic actions as a troll:

http://nm.merz-akademie.de/~stefan.krappitz/

—

Edited by Cristina Vremeş

Comment

[...] conversation with the author (Matei Samihaian, Pool) [...]

[...] eine eigene Ethik verfügen. Die Keynote der kostenlosen Veranstaltung spricht der Trollexperte Stefan Krappitz. Er hat seine Diplomarbeit dem Thema “Troll Culture” gewidmet. Da die Veranstaltung [...]