12.28.11

Post-Internet Painting and the Death of Affect

1. Art Blog, Art Blog

What are the implications of taking a web-based project into reality? Painter Joshua Abelow, whose blog Art Blog Art Blog has been running since March 2010, was curious what his blog would look like in three dimensions. Taking curatorial residence in well-known Op artist Ross Bleckner’s studio in Chelsea, Abelow chose curators to mount shows for two weeks at a time, keeping with the garrulous pacing of his website. He named it Art Blog Art Blog, intentionally conflating the blog with the gallery itself.

Last month, I asked Abelow about his project over gchat. He told me, “Initially the blog was a way for me to contextualize my own work alongside artworks and text by other artists and writers i was interested in, and it still is that,” he wrote. “But it’s also a way for me to curate in the simplest way possible[…]To call a gallery space a blog is something that had never been done before; and I think it generated a lot of interest because of that simple gesture. It created an element of confusion — like what is ART BLOG ART BLOG - a gallery, a blog, or a website? And, for a temporary period, it was all three.”[1]

Abelow does not distinguish between these projects and his painting practice. The Internet functions as less of a subject matter for his work, but “a tool of empowerment. Since nobody else was going to put one of my paintings in a show next to a Francis Picabia i figured i would just do it myself.” His paintings poke fun at the relationships between the curator, the collector, and the artist, sometimes assuming the roles of all three. He is prolific like Josh Smith and in a similar way, his practice is responsive to a technological context; his oeuvre, documented extensively on his website, constitutes a single work. He is Michael Krebber-ish, although Krebber interacts with blogging in his work differently. Krebber’s paintings are networked, and appropriated, like the Internet itself. In a contemporary art world throttled by the Internet, painting is a special case, as it is uniquely suited for a slippage between representation, simulation, image, .jpg, and object. Abelow’s projects engage this aspect.

On ABAB the blog, (www.joshuaabelow.blogspot.com), paintings, poetry, and sculpture are liberated from their contexts, allowed to rub shoulders with each other and make conversation in a situation of the blogger’s choosing, and in Abelow’s case, sometimes to surprising or humorous ends. The blog’s ability to level the playing field – create a horizontal, rather than vertical, relationship between the works — was an idea Abelow carried into his exhibition strategy. With the gallery, he “create[d] a situation where well known artists were showing alongside artists with very little or no public exposure.” Art Blog Art Blog was a critical project, investigating the intersections between the real and virtual world, and especially the increasing reach of the virtual.

2. JG Ballard’s Death of Affect

The gallery’s ninth exhibition, ‘The Death of Affect[2]’, seems to be a direct result of Abelow’s critical agenda and technological preoccupations. It was curated by New York-based artists Jeffrey Scott Mathews and Fran Holstrom, who made their choices loosely based on JG Ballard’s short story from 1961, The Overloaded Man. Ballard was greatly concerned with how our relationships to media in capitalist culture influence our ability to emotionally connect with ourselves and others. In 1974, Ballard coined the phrase ‘Death of Affect’ to describe a condition where humans are incapable of experiencing feeling, a result of the crippling pervasiveness of media. Ballard’s text is ever more relevant in the Internet era.

In the story, the protagonist is (ironically) named Faulkner, a disgruntled husband living in a futuristic housing complex. One day he accidentally discovers a new talent: a way to contort his reality into abstract forms.

The houses opposite had vanished, their places taken by long rectanglar bands. The garden was a green ramp at the end of which poised the silver ellipse of the pond. The veranda was a transparent cube, the centre of which he felt himself suspended like an image floating in a sea of ideation. He had obliterated not only the world around him, but his own body…[3]

Faulkner sets an alarm to jolt him back to reality, but each time, “a screen still separated them, its opacity thickening imperceptibly.”

As the story progresses, Faulkner descends deeper into madness. Object by object, he continues to drain objects of all until he exists in a “cubist landscape.” Finally, he abstracts his wife, erasing all subjective connotations: first, he “[forgets] her hands, forever snapping and twisting like frenzied birds” and promptly “[lets] her fall to the floor, a softly squeaking lump of spongy rubber.”[4]

In the 1974 introduction to his novel Crash, Ballard describes the death of affect as symptomatic of 20th century’s media-driven culture: “the marriage of reason and nightmare which has dominated the 20th century has given birth to an ever more ambiguous world…” resulting in “the most terrifying casualty of the century: the death of affect.”[5] Critic Steven Shapiro elaborates: “[According to Ballard], thanks to the new electronic technologies, the world has become a single global marketplace. Universal commodity fetishism has colonized lived experience… Every object has been absorbed into its own image. There is no longer (if there ever was) any such thing as a single, stable self.”[6] When the protagonist in the story presents his discovery to his neighbor, he responds, “The subject-object relationship is not as polar as Descartes’ ‘Cogito ergo sum’ suggests. By any degree to which you devalue the external world so you devalue yourself.’[7] There is much at stake.

3. Death of Affect (exhibition)

The curators Holstrom and Mathews chose works that address the impact of technology on individual subjectivity. I chatted with them online at length last month about their decisions for the exhibition.[8] Wrote Mathews, “We thought this story, and the theory surrounding it was the perfect analogy for a condition of media saturation… I think our goal for this show, and of the artists whose work we included in the show, is to illustrate the possibility of the death of emotion.”[9] This death results from, to Mathews, the systemization of our relationships to “anything an everything, people, objects/forms,” the more they become more familiar, individualized, “the more they distance each person from their individuality… this is total media domination… when media seeps into your dreams, your subconscious, where else can you go?”

The works in the exhibition, all relatively recent (the oldest from 2005), and mostly traditional media (painting and sculpture), each explore the relationship between affect and image, and how it has developed since the 1960s.

Holstrom brought up Wilson’s work when we discussed the personal relationship we have with images on the Internet, and accompanying questions of authenticity, subjectivity and authorship. Wilson takes all the images she uses herself. They have a postcard like perfection. “Most of us assume they are lifted from the Internet, etc,” wrote Holstrom. “But she rustles about in the woods, desert, etc to get these perfectly sublime images of nature, and then she tranforms them (not in color or tone) by drawing attention to their previous flatness as images, and giving them a new life.” Wilson’s subjective identity, interred in the photographs, is not immediately available to viewers, yet it is crucial to understanding them. The sculptures comment on the ubiquity of images and the stratification of one’s identity through photography on the Internet. “[It’s] like every sunset is a piece of stock photography even if you are alone on a cliff with the wind in your hair. we still experience it together…..” Media affects how we experience life itself: “We almost don’t see the beauty of everyday life anymore, we are always thinking about how to maximize the experience via Twitter, etc.” The work recalls Don Delillo’s “most photographed barn in the world” from White Noise; in a maze of representation, we go to the barn only to photograph it. Wrote Holstrom, “[it’s] as if there is no longer you or I but an expectation of shared experience.” Wilson seeks to recognize, and reenergize, the subjective identity of both the artist and the viewer. Her photographs, that would be ubiquitous on a Facebook page or Google image feed, are fleshed out into the real, reified, there for us to trip over like we would a rock on a hiking trip.

Dannielle Tegeder’s sculptural installation consists of objects swathed in black cloth displayed on a shelving unit. The objects are sometimes recognizable, but often elude association. Holstrom wrote of the piece, “the viewer is invited to participate in the display and then, then not allowed to fully engage in knowing the objects…very trippy, almost Pavlovian.” The movement of the forms between recognizable and non-, shapes in a composition and actual objects, resembles the transformations of Ballard’s character, the blurring between image and object. Tegeder very simply and swiftly transforms a well-known object into something unknown, mysterious — an effect also produced by the digital sublime.

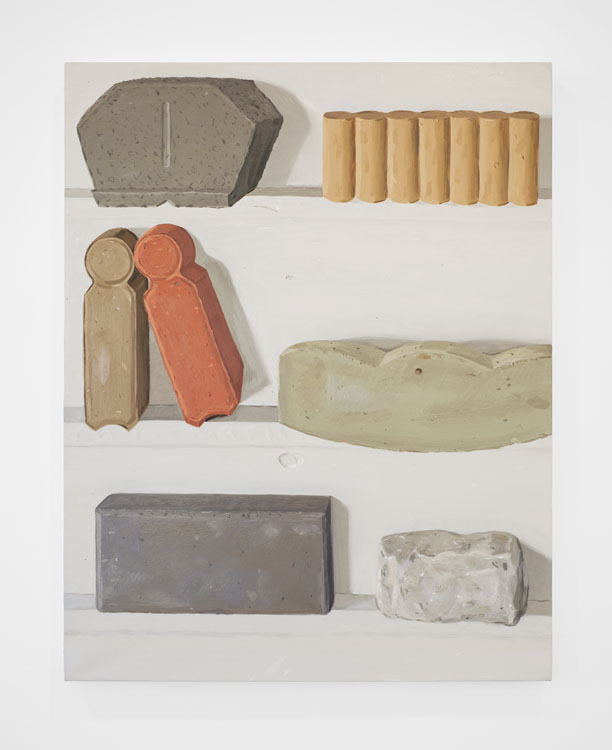

Three painters in the show combine realism and abstraction. Halvorson’s painting, Edging, also touches on the uncanny, presenting objects that are at once exceedingly familiar yet frustratingly distant with a Surrealist bent. Minuscule details, results of fastidious plein air painting, describe the objects’ surfaces, but appear unrelated to their makeup or shape. As a result, the surfaces read more like ‘surface treatments,’ like digital ‘skin’ overlaid on the ‘mesh’ of an object to better describe it. These details alone are the identifiers to the objects. It is a representational painting, but Halvorson treats it like an abstract; each realistically painted, but completely unknown, object is flattened by lack of recognition into a shape. Similarly, JJ Garfinkel’s paintings wrestle with figuration and abstraction, producing a puzzling image where space is distorted by folds in a pastel-colored veil. Gina Beavers’ painting literally superimposes both methods, denying the illusionistic depth of a laundromat interior scene with a goopy outline of a neon sign, collapsing technological, painterly, and graphic representational strategies.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is Mike Cloud’s ‘Chicken with Two Stars of David’, from 2005. Chicken Limbo is a plastic toy from a children’s game with long orange legs and a dangling tail. Its feet are drilled to two square paintings of the Star of David. One struggles to identify the sociopolitical statement, if one exists; is it about the Jewish politics? Cloud appears to disregard any and all associations the objects might have. Like Albert Oehlen paintings from ’04-’06, he investigates the weight of the empty signifier. Unlike Oehlen, he resourcefully elicits a nostalgic response from a certain type of viewer, one of middle-class, mid-90s upbringing, now the young twenty something. This surge of nostalgic affection and resulting humor is immediately suppressed by the specificity of the Star of David, and its heavy symbolism. Mathews summarized, “for something so cloaked in symbolic meaning, it seems overly symbolic… almost cancelling its agenda.” The sculpture is like a tumblr feed (even though it was made pre-tumblr), or a Google image search, creating a bizarre juxtaposition. (What would the search term be?) Encumbered by its specificity, it collapses under its own symbolism.

For Holstrom, Cloud’s sculpture represents a reinvigoration of individual subjectivity. The structure supports itself by way of a figure; the paintings wouldn’t be visible without it. “It is about the necessity of a figural support[…] i think of the chicken as a comical stand-in for the potential viewer.” In doing so, Cloud restores the authority of a subjective viewer, while simultaneously waylaying the sociopolitical and affective connotations of the paintings and toy. “its like a struggle, which is more important, the figure (toy/us) or the images?…We are mutually dependent.”

What is the role of empathy in contemporary society subjugated to a constant deluge of images? We increasingly forge affective relationships with images, brands, representations, advertisements, media, rather than with our own images. We are ‘just pagans engaging in idolatry.’[10] This is not anything new. Yet we find our subjectivities increasingly codified by powers outside our own. And why paint? A sort of anachronistic frission exists in artists using traditional media to explore ideas around technological alienation. Digital media feels too correct, too close to what they’re trying to critique.

In the 1980s, painters like Sherrie Levine, Ashley Bickerton, and Vaisman and Wasow explored similar themes, responding to the proliferation of television and advertising. In Signs Taken For Wonders from 1986, Hal Foster suggests that by combining strategies of both representation and abstraction, they created simulations in order to criticize the abstractive tendencies of late-capitalist society. “The duplication of events by simulated images is an important form of social control, as important today as ideological representations. In fact, simulation, together with the old regime of disciplinary surveillance, constitutes a principal means of deterrence in society…In short, more than this or any art, is the abstractive processes of capital that erode representation and abstraction alike.” More than twenty years later, the artists in the Death of Affect struggle with the same issues. And “Death of Affect” isn’t the first exhibition to tackle Ballard’s themes—“Crash: Homage to JG Ballard” was at Gagosian in Spring 2010, with selected work which explored Ballard’s themes of “psychological effects of technological, social and environmental developments on humans.”[11]

I am not entirely convinced of the hierarchical relationship between our affective relationships to real objects and their counterparts, ‘evil’ media representations. We have always had images that we are emotionally connected to. We have meaningful experiences and connections online. Abelow’s Art Blog Art Blog project showcases the liberating and boundary-erasing power that images, used in the right way, can contain. In contrast, Ballard presents a dystopic world where representation has replaced the real.

At the conclusion of The Overloaded Man, the protagonist passively murders his wife and then drowns himself. Yet Ballard ends the story on a relatively positive note: freed from consumer culture, the weight of associations, history, he is unburdened:

“At last he had found the perfect background, the only possible field of ideation, an absolute continuum of existence uncontaminated by material excrescences…he waited or the world to dissolve and set him free.”[12]

[1] From interview with Joshua Abelow, November 20, and December 7, 2011

[2] “affect” (aff-ect) in psychology, see also affect theory, is generally thought of as an emotion or feeling, but one that is subjectively experienced.

[3] The Overloaded Man, in The Complete Stories of J.G. Ballard, hereafter refered to as ‘Stories,’ 247.

[4] Stories, 253.

[5] J.G. Ballard, introduction to the French Edition of Crash, 96.

[6] Steven Shapiro, The Life, After Death, of Postmodern Emotions, in Criticism, Winter 2004, 126.

[7] Stories, 247.

[8] Disclaimer: I did not get a chance to see the exhibition in person but have seen some of the work by the artists before. Using the images, and the press release, as a form of visual research, I ignored how I might subjectively experience the work coming upon it in reality, and probably missed important details. Working with the curators, however, I was able to get a better picture of the works.

[9] From interviews with Jeffrey Scott Mathews, December 12, 2011, and Fran Holstrom, December 3, 2011

[10] Jeffrey Scott Mathews’ words, referencing Dave Hickey lecture, ‘The Evils of Creationism: Art History According to Darwin’

[11] Press release for ‘Crash: Homage to JG Ballard’ February 11 – April 1, Gagosian London, 2010 http://www.gagosian.com/exhibitions/february-11-2010-crash

[12] Stories, 254.