05.04.12

F/F

Fotolog reached its peak in 2008 with over 30 million registered users, primarily from Chile, Argentina and Brazil. As a standard photo-sharing platform, it wouldn’t be worth writing about if it wasn’t for the magnitude of its usage and cultural consequences. Fotolog became a trend, a symbol, a brand [1], a tribe. In Argentina and Uruguay, Fotolog users were known as “floggers”, representing a generation of open-minded, sexually tolerant, and educated teenagers. In Chile, they called themselves “Pokemones”. While Pokemones were influenced by Japanese culture, they shared many interests with floggers, such as apparel and hairstyle. From head to toe, the Flogger and the Pokemon were easy to differentiate from other subcultures, such as Punks, Goths and Emos, even though their aesthetics were an amalgamation of many of these groups. This sartorial overlap was something that led to the many infamous fights between old and new tribes outside the malls of Buenos Aires [2], Santiago and Montevideo; similar to those viral Emo vs. Punks confrontations in Mexico. The disputes, far from merely being kids fighting over clothing, were evocative of South America’s evolutionary and transitional stage. It wasn’t all about the hair; Floggers, Pokemones and Emos were androgynous youth who threatened the established patriarchal and homophobic South American culture. These groups represented that half of the southern cone’s youth that came from an Europeanised middle class. This resulted in attacks, harassments, abuses and even murder in Argentina– in 2008, a 16 year old was kicked to death outside of a club by a group of teenagers from an opposing tribe, the Cumbieros.

1.

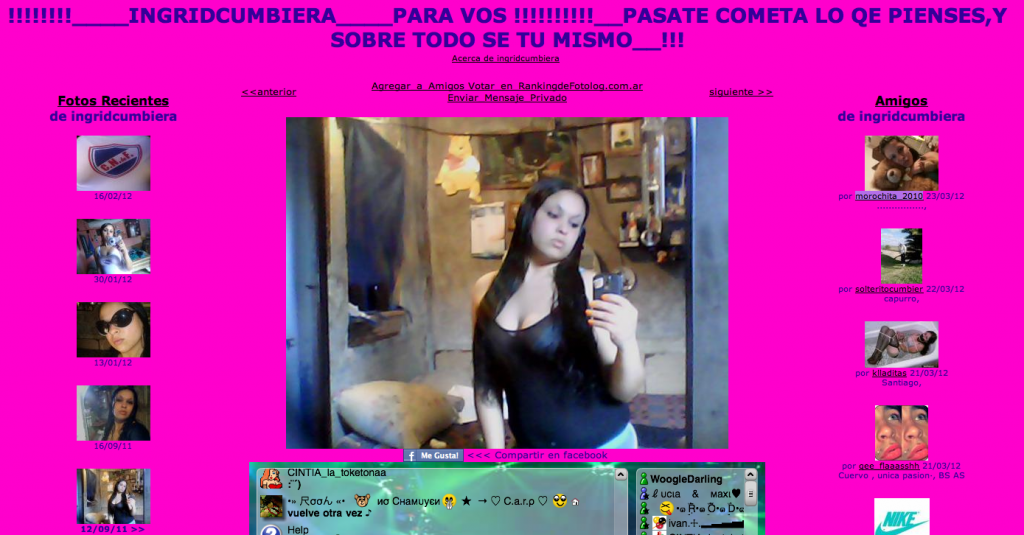

Fotolog was particularly addictive due to its restrictions. Limited daily to one picture, 20 comments, one layout, a colour chart and a 520 x 410 px Oeil-de-boeuf, the platform succeeded because of it’s game-like set of rules. Its structure encouraged consistent daily use, which became the epicenter of its allure. Fotolog forced anyone with the aim of maintaining a current blog to adhere to a fastidious uploading routine. If the opportunity to update was missed, the rewards would not be reaped. To keep a popular profile, one had to commit to strict, regular posting– once a day, every day. Similar to Facebook “likes”, the finite amount of comments made the 20 signatures a currency, a goal that had to be achieved regularly for the sake of nurturing one’s online persona, leading users to overproduction, a constant desire for renovation aided by new photos and special effects. A aesthetic commonality between the most popular Fotolog users gave birth to the Floggers as a tribe or style, dictating the hair, the outfits and the musical tastes of the winning combination for popularity. It was a blend of mid 2000´s European teen fashion, electro dance music, plus some elements from Emo and anime culture.

This competition for attention was derived from the anxious ambition to provide entertainment and garner popularity through updates. Cultural capital manifests itself in virtual environments just as it does physically. Social inequality and class become apparent online as much as offline, frustrating the optimistic expectations of the net as a utopian playground in favour of a digital mirror of people’s offline realities– a conglomerate of social networks. The colours and the fonts, the writing and the grain, all functioned as indicators of social class and background, transforming the semiotics of the interface into a decisive factor in the nature of one’s social interactions.

2.

In the crowd, a feeling of insecurity discomforts. Although users cannot live in cyberspace alone, the necessity of a dwelling and the need for belonging, make the building of a community a solution for uprooting, for uncertainty. While we dwell plurally, we do it separate from the others, the strangers, protecting ourselves from the hostile. Gradually, certain groups flourished in Fotolog, cliques formed and communities emerged in parallel with those forming offline. A hierarchy took shape, mirroring the two halves of the population– the higher and the lower. In a dynamic in which the peripheries constantly tried to become the hegemony, the formation of a new photo sharing platform took place under the name of Fotocumbia.

In 2008, the creation of this bootleg version of Fotolog functioned as a statement against the rules of the original, including total freedom of content (pornographic images welcome), unlimited photo uploads, music and an embedded chat room. It was an online embassy for the Cumbieros, an uprising against a system that didn’t accept them.

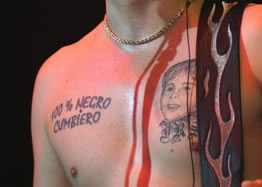

While floggers were a representation of the 2000’s South American flippant youth, which rebelled against the old establishment with a queer attitude, they were still middle class– they played by European rules and were intolerant of their poorer and darker skinned contemporaries. On the other hand, the Villeros, the Cumbieros, emerged from a much lower social class. Many of them were immigrants (or from immigrant backgrounds) from rural sides of the Patagonia and from other Latin American countries. They rejected the Europeanised and Americanised aesthetics which were considered the top of the cultural hierarchy. Claiming a new style to represent their people, with tropical and Latin American beats, they also embraced the stereotypes that made them repulsive to their wealthier peers by using violent lyrics, politically incorrect attitudes towards women, homophobia, antagonistic attitudes towards authority, and explicit references to drugs– portraying the reality of their situation as outsiders.

Floggers were the ambassadors of a Eurocentric identity, while Cumbieros were the enraged other, agitated by cynicism. The restricted access to the Villa Misera is a lock, a bolt that protects one class from the other. By not allowing the access to any outsider and by inverting the criteria generally applied outside of it (in the high-street, downtown), the community protects itself and generates its own economy of cultural capital. The fortress shelters daydreaming, the fortress protects the dreamer, the fortress allows one to dream in peace; the community protects the dreamer, and the dreamer creates it’s own content [3]. The dreamer succeeds in removing herself from the periphery and takes a place at the top of a hierarchy of her own creation. The nihilistic aura of the Cumbia Villera was said to be a descendent of Tango, which also started in arrabales (poor quarters of the City of Buenos Aires) and was sung in the immigrants’ slang, the lunfardo (mix of Spanish and African/ Italian expressions). Being a style that ultimately became a legitimate national symbol of identity, it’s not surprising that the initially despised Cumbia Villera music and style were later popularized into an acceptable depiction of the unprivileged. Carlos Tevez, who signed with Manchester United in 2007, had cameos in a few Cumbia Villera shows and was always vocal about his upbringing in the Fuerte Apache. Pablo Lescano, frontman of Damas Gratis, precursor of the Cumbia Villera, was awarded the Clarín Prize [4], invited to perform on Susana Jimenez’s TV Show [5] and played at the MTV awards in collaboration with mainstream performers. Their music portrayed Argentina’s reality as tango did before it. It was accepted, saluted and respected.

3.

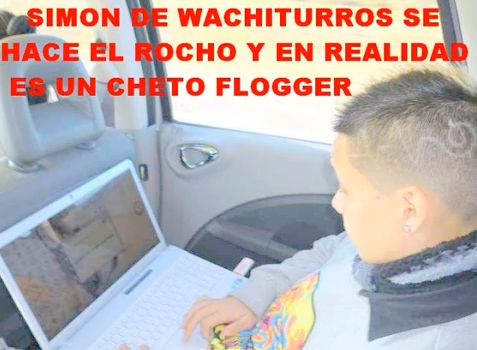

Every trend has a trajectory and lifespan– a rise and fall, an appropriation and repackaging. The only way for the Cumbia Villera and the Cumbieros to be accepted by the establishment was to lose their original meaning and become a commodified aesthetic. In 2011 Fotolog had plans of changing the layout that made it famous (and which Fotocumbia copied), Fotocumbia was rotting and malfunctioning with bugs, Cumbia Villera was praised and played overseas in cultural events [6] while being diluted through religion in the mainland [7], Floggers barely existed anymore, and a band called the Wachiturros came to life. The Wachiturros are a boy-band of dubious quality, who proclaim themselves to be Cumbieros, Rochos and turros [8]. They were immediately featured on TV, played at theatres like the Gran Rex [9], garnered hordes of fans and manufactured merchandise– all of which rapidly led to the creation of a new subculture. They were soon hated by many. Viral videos and posts made reference to their past as floggers, and a new label was created for this new style, the one of the Flogger or the Cheto Arrepentido (Repentant Posh Kid). The Wachiturros and the Chetos Arrepentidos dress like Villeros, dance Cumbia but invert the symbols. By not singing about the topics characteristic of the slums and distorting the aesthetic by adding a queer element, the Wachiturros act as a subversive agent [10].

To dance in front of the real Rocho or Turro, copying his clothes but wearing lipstick, is an attack to the only valuable thing the Villero possess: genuineness. The Chetos Arrepentidos play with this disrespect towards the holiness of the fortress, making themselves a target for abuse and violent attacks, from online bullying to physical aggression. Sexuality aside, the fight is about realness, about the legitimacy of class, a struggle against artifice and a desire for a singular style. The thing that was now accepted was the visual, and not the original context. While Cumbia has been repackaged and made ready to sell, it’s origins remain untouchable and restricted, its reality rarified. The never-ending list of videos in which a critique is being made against the Wachiturros or the Chetos Arrepentidos evokes the voice of the defeated. They are made by those claiming to be genuine in an attempt to raise awareness of their legitimacy and that which threatens it.

Class imitation becoming class aversion and vice versa has existed throughout history. The cycling of trends continues, macro-scaled by the sampling without crediting of third world beats and in the way in which underground styles are appropriated and commodified by the middle and upper classes. In a sea of dromology velocity wins and superficiality is easiest to digest. Class warfare pushes content to be easily absorbable, removing any trace of criticality. With content appropriated and the originator pushed aside, the need to be protected against alienation arises. Once again, the outsider builds a shelter where she can feel safe, protected. The dreamer creates new symbols and new content in a never-ending attempt to reach the centre from the periphery.

—

[1] - In Spanish the word Fotolog is used to define any sort of photo blog.

[2] - Abasto, a Mall in Buenos Aires, was the IRL meeting point for the floggers.

[3] - The use of the word ‘fortress’ is not unintentional. El fuerte Apache (The Apache Fort) is one of the most famous re-housing projects in Buenos Aires.

[4] - Clarín, the largest newspaper in Argentina. The Clarín Prize, is an award program that have taken place since 1998 and honours Argentine achievements in entertainment, sports, literature, and advertising.

[5] - Susana Jimenez’s TV show is to Argentina what Oprah is to the US (?)

[6] - In 2011, a cultural event from the Paris-Buenos Aires Tandem, concluded with a session of Cumbia Villera, at the Centre 104, Paris.

[7] - At the end of the decade, Cumbia Villera’s violent and explicit lyrics turned into more pop- like, romantic and friendly topics, after an intense process of evangelisation.

[8] - Guachos and Turros are Argentinian words from the Lunfardo, meaning bastard, shameless.

[9]- The Gran Rex, which opened in 1937 as the largest cinema in South America, is today one of Argentina´s biggest venue for the staging of international shows.

[10]- Similar to current Chav aesthetic, first appropriated from the underclass by the gay community via fetichization, and currently made trendy through tumblr aesthetics.

* Those parts of the text which are in italic, are modified excerpts from Bollnow’s Human Space and Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space.

Bibliography

Bachelard, G. (1992) The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

Bollnow, O. F. (2008) Human Space. Hyphen Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction, A social Critique of the Judgement of Taste

Frikipedia http://www.frikipedia.es

Heim, M.R. (2001) The Feng Shui of Virtual WorldsPDF

Llobril, G. (2002) Del Tango a la Cumbia Villera (From Tango to Cumbia Villera) PDF

Loquendo, J http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gHmz4hZaJG4&feature=related

Miceli, J.E. (2005) La Cumbia Villera Argentina PDF

Rheingold, H. (2000) The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. MIT Press.

Written from the perspective of an expat.

2011-2012

Comment

hay bb!!!

que linda colita!!!

bienvenida!!!

pase…pasate

pasate bb hermosa!!! te espero por el mio… mas linda te ves!!! si te copas dejame tu msn!!! tas en mis effes… sobes donde te gusten!!! babaaaaaaaa

q cola mami:)

Graciias X Pasarte Preciiosa!(L

Un Besiitoo Bombom… Pasate Cuamdo Quiieras =)

Tu Eme ? =$